HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

Americn Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet Publication

Version 061411

THE BRADSHAW BROTHERS AND THE BRADSHAW TRAIL

By Kathy Block

APCRP Historian

Bradshaw

City and its cemetery, and Isaac Bradshaw's grave, have been discussed in several

fine APCRP articles.

They touched on the history and lives of two intrepid men who expanded a trail

that became the Bradshaw Trail thru Southern California. The brothers ran a ferry

across the Colorado River. One of them pushed on into the mountains of Arizona.

Here is more of the story of Isaac and William Bradshaw, true pioneers of the

late 1800s in Southern California and Arizona. I was able to access original

documents, later quoted by others, via a vigorous internet search, adding

interest and depth to their history.

William

David Bradshaw was born in Tennessee around 1826, but then lived in South

Carolina. He may not have been married. His tragic death on Dec. 2, 1864, in La

Paz, Arizona, will be discussed later.

His older brother, Isaac Bradshaw, was born in

1819 in North Carolina. Isaac married Frances Burdette Combs on Aug.22, 1843,

in Johnson County, Missouri. The 1860 Santa Rosa, Sonoma County, California

Census lists Isaac, age 41, as a married white farmer; wife Francis B., age 34;

and two children, Maria age 13 and Francis age 9, both born in Missouri. Isaac

died of pneumonia on Christmas Eve, Dec. 24, 1885. Francis had applied for a

homestead in Sonoma County on May 14, 1866, and she (nicknamed Fannie) lived in

Santa Rosa, California by 1870 with her daughter and son-in-law, John W. and

Maria Bradshaw Combs. She outlived Isaac, dying in Santa Rosa of ulceration of

the stomach at age 70, Oct. 14, 1894, and is buried in Santa Rosa. Isaac is

buried in a remote area of the Bradshaw Mountains near a riparian area at

Bradshaw Springs. The couple apparently had lived apart for many years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

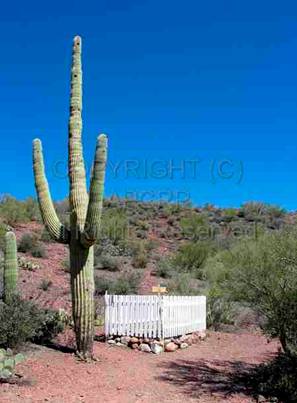

2006 Photo’s of

Isaac Bradshaw's Grave, Courtesy of Neal Du Shane

An original

document: Reminiscences of a Ranger; or Early Times in Southern California by Major

Horace Bell, (1830-1918) was written in 1881. Bell headed Chapter XXVII about William Bradshaw with “Bradshaw-A

True Gentleman and Natural Lunatic”. Bell's description of William Bradshaw,

often quoted by later writers, is classically florid: “(Bradshaw) was one of

nature's most polished gentlemen and brightest jewel in America's collection of

true born chivalry. (He) was brave, generous, eccentric, and in simple truth a

natural lunatic. In manly form and physical beauty, perfect; in muscular

strength, a giant; in fleetness of foot and endurance, unequaled.”

He

began his account with “Bill” turning up in Sonoma in 1846. He was 20 years old

and working for Captain Salvador Vallejo, Mexican Post Commander, building a

picket fence. In an argument over how the fence was being built, this “despotic

authority” hit Bradshaw with the flat of his “Toledo.” Bill struck back with a

redwood picket, knocked the captain down, seized the sword, and pounded it into

“pot-hooks” with his axe! Bradshaw

realized what he'd done, seized his rife, and hastily headed for the Sacramento

Valley, only to return when this military post fell to the California “Bear

Flag Party”, in 1846, after the start of the U.S. Declaration of war against

Mexico on May 13, 1846. The commander, Vallejo, recognized Bradshaw and

supposedly said that “now I suppose I will be murdered, finding this assassin

in your force.” Bradshaw replied that an American never strikes an enemy when

he is down, shook Vallejo's hand, and promised him his friendship.

In

1847, after many adventures, Bradshaw was in Los Angeles as a Lieutenant in

Fremont's Battalion. He was noted there for his “wild freaks that astonished

the Dons and won the hearts of the Donas, among whom he was a universal

favorite.”

Next,

in 1851, he was involved in a French revolution at Mokelumme Hill, an early

mining site. A large French colony there refused to pay a “foreign minter's

tax” passed by the State Legislature. The French miners defied the power of the

sheriff and then the State to collect this tax.

Bradshaw commanded a battalion of militia and avoided an armed battle by

approaching the French commander and proposing that if blood was to be spilled,

let the question be settled by single combat between the two commanders. In the

end, this led to an amicable adjustment, the French rebels pulled down their

tri-color flag, and peace was made, especially when it was explained the tax

was to apply only to Chinamen. A note on the treatment of the Chinese miners

was that “the Chinamen, were vigorously pursued and made to feel the full force

of the law in filling the pockets of the Collector and his legion of deputies,

for very little of the gold wrung from the non-resisting Mongols found its way

into either the county or State treasuries!”

William

Bradshaw was called “Bunk” (from the fact he came originally from Buncum

County, South Carolina) and was, according to Bell, one of the “most witty

fellows to be found, and wherever he stopped a crowd of eager listeners would

surround him, and roars of merriment would respond to his well-turned points.”

One example, while he was in San Francisco, occurred at a dinner party. Someone

passed a dish of shrimps to him. He held the dish of shrimps in one hand and

said he'd never heard of a shrimp before, though he'd eaten “snakes, feasted on

lizards, and gormandized on grasshoppers.” He took a large handful and ate

until he finished the whole dish, shells, claws and all.

When

William joined the Sonoma garrison to enlist in August to join the revolt,

Isaac Bradshaw moved his family at that time to California. But, after 1862, Isaac left his wife and

children in California to join his brother William in operating a ferry across

the Colorado. Before that time, though,

news of Pauline Weaver's discovery of gold at the Plomosa placer mines in La

Paz reached California, in 1861. William decided to explore the gold fields for

himself!

In the

spring of 1862 William Bradshaw led a party of 8 men to the Plomosa mines. He

was determined to locate a shorter, better route. The existing routes to

Arizona required going a great distance southeast to Yuma, crossing the river, and

then north up the river to La Paz. He

and his party traveled an existing trail thru San Gorgonio Pass to the Salton

Sink. There, several Cahuilla villages were located and he befriended a

Cahuilla Chief named Old Cabezon and a Maricopa Indian mail runner from Arizona

who was visiting. The two Native Americans gave Bradshaw a map of ancient

Halchidoma Indian trade routes thru the desert, with the location of springs

and water holes, ending at the Colorado River near present day Blythe,

California.

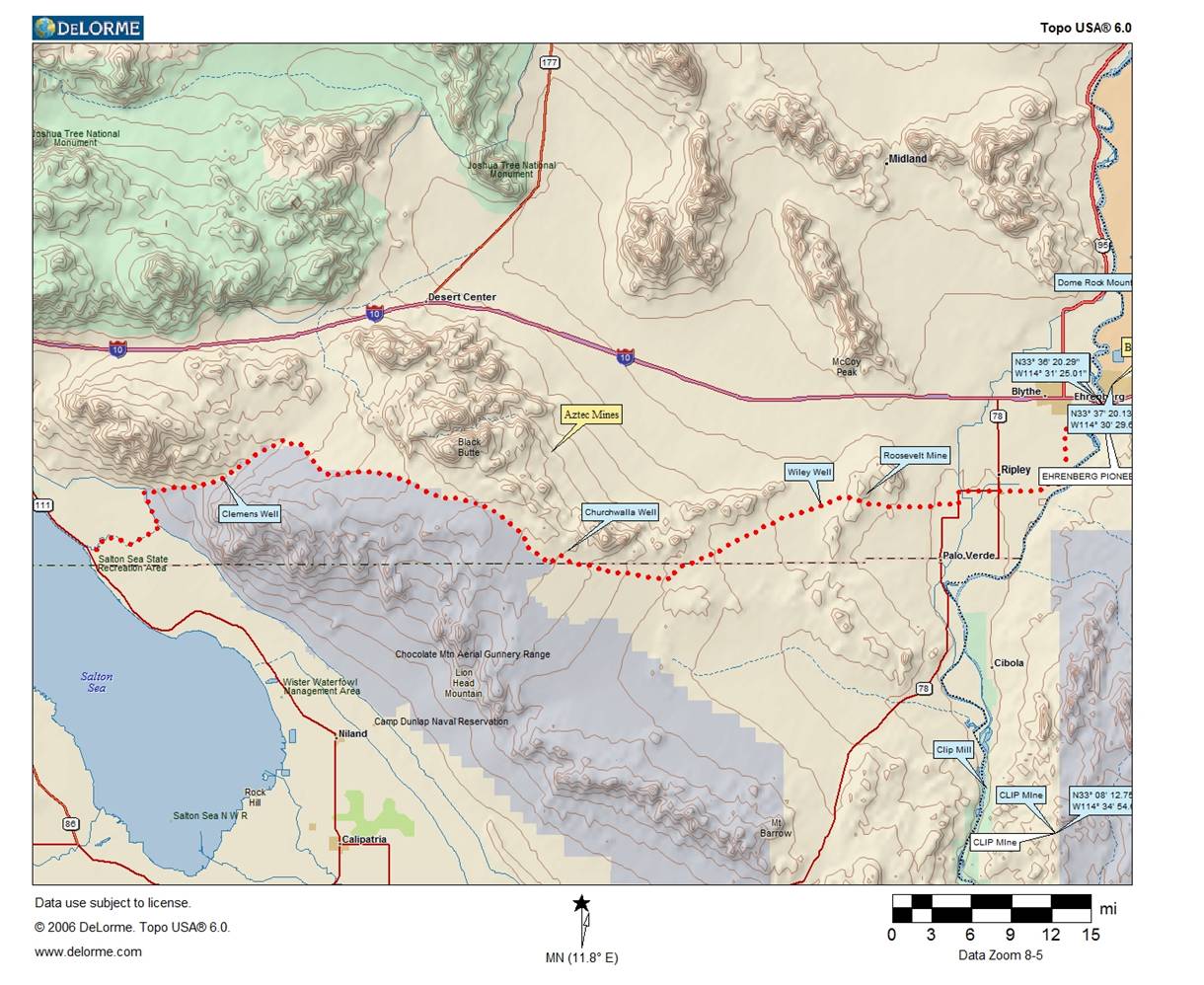

The

route developed into the Bradshaw Trail. It was originally 180 miles long and

began east of San Bernardino in the San Gorgonio Pass. It went southeast thru “Agua Caliente”, now

Palm Springs, then south to the region where the Cahuilla Indians lived.

Bradshaw traveled east near present day Mecca at the northern tip of the Salton

Sink, to the foothills of the Orocopia Mountains, then to an existing stage stop called “Dos Palmas

Springs.” The trail continued east thru a pass between the Orocopia and

Chocolate Mountain ranges, around the southern end of the Chuckwalla Range,

crossed thru a gap in the Mule Mountains, and reached the Palo Verde valley two

miles southwest of the present community of Ripley. Water holes were found at roughly 30 mile

intervals at Canyon Springs, Tabaseca Tanks, Chuckwalla Springs, and Mule Spring.

Ed Block at

Chuckwalla Spring May, 2011.

The stone wall

around the dried up spring was erected to trap water for sheep and other

wildlife

Only damp mud

remained at this time

One

traveler, named Marion Dickerson Fairchild, and a friend, traveled this route

in August 1862. They traveled 11 days and still had 60 miles to go on the route

that Fairchild described as “the road” and “the beaten path.” They obtained

“good water” at Chuckwalla Springs. They were followed, a few weeks later, by

the first large group of miners. There were 150 well equipped miners and they

traveled the entire route without loss of a man or animal. Pack trains and

freight wagons began using the trail as soon as it opened. In the middle of

September, 1862, the first stage line began. The stage operated from Los

Angeles to La Paz and was named “The Colorado Stage and Express Line.” It was

owned by David Alexander. The “coach and six” trip took 4 to 5 days. For only a

few weeks the stage operated regularly, carrying passengers for a $40 fare. The

Concord coaches could carry 9 passengers inside and 6 more on the roof! At

times more people were crowded on the stages. One carried 35 people, counting

the driver and “shotgun” rider.

Ridership declined with the peak of the gold rush, and in 1863 the stage

was replaced with a mail route from Los Angeles to La Paz, then north to

Prescott, and east to Santa Fe.

The

trail veered northwest to a crossing of the Colorado River north of what is now

Blythe, California, and then on the Arizona Territory side it went approximately

4 miles upstream to the gold fields of La Paz. The trail became the main route

between Southern California and these gold fields of La Paz and other places in

western Arizona between 1862 and 1877. In Arizona, it later roughly went east

along the present route of Interstate 10, towards Wickenburg. Then, various

trails went north into the Bradshaw Mountains which are named after William Bradshaw.

Map of the Bradshaw

Trail, Courtesy Neal Du Shane

The

Bradshaw Trail, as it came to be known, was an ambitious enterprise for moving

passengers and freight, because at least half the route would be thru uncharted

desert washes and mountains. Water made the difference, as it was more

available compared to other routes thru the desert. Wells, such as Wiley's

Well, were developed when the distance between springs was more than 35 miles.

The route shortened the trip to the gold fields by at least several days and

soon became recognized as the primary route to the gold fields, at La Paz.

|

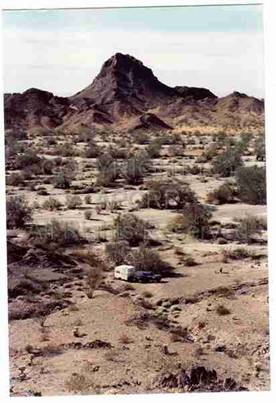

Looking

SE in Chocolate Mtns, Bradshaw Trail in distance |

Old

bombs along Bradshaw Trail at edge of Navy Bombing Range, Chocolate Mtns. |

|

Chocolate

Mtns, Looking north towards Imperial Gables |

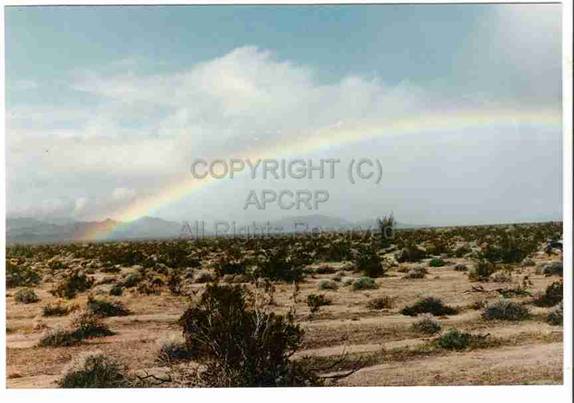

Miners

traveled the Bradshaw Trail past the Little Chuckwalla Mtns, CA. Seeking

a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow |

Some of

the travelers along the Bradshaw Trail were miners and explored and prospected

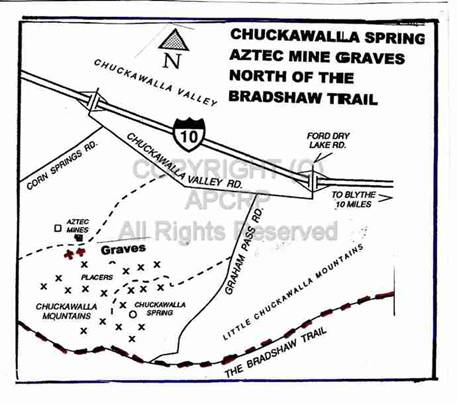

in areas mainly north of the trail in California. One such effort may have been the Aztec

Mines. These mines are located several miles north of the Bradshaw Trail in the

Little Chuckwalla Mountains, not far from Chuckwalla Spring. We found three male graves on a plateau

directly below ruins of mine buildings. These could have been people who died

near the trail or miners from the Aztec Mines. The graves are a reminder of

harsh conditions faced by the early Bradshaw Trail travelers as they pushed

eastward towards Arizona.

Ruins at Aztec

Mines

|

One

of several male graves found on a plateau below mine ruins |

Aztec

Mines, graves and Chuckwalla Spring, in

relation to Bradshaw Trail |

When

men and animals using the Bradshaw Trail reached the Colorado River, they

needed a safe way to cross. On November 7, 1864, the first legislature in

Arizona granted to Isaac Bradshaw an exclusive ferry franchise on the Colorado

River “at any and every point between what was known as Mineral City and a

point five miles above La Paz.”

William

Bradshaw and his brother Isaac Bradshaw and William A. Warringer, owners, ran their

ferry, from Providence Point, on the California side to Olive City on the

Arizona side. Olive City was about 6 miles south of La Paz and was named for

Olive Oatman. Earlier ferries had been simple rafts of tulles (bulrushes) rowed

by Native Americans. Bradshaw's ferry was a rude boat attached to a rope

spanning the Colorado. The boat could carry wagons and a limited number of

animals, and the current was the propelling power.

Here

were the rates in 1862 for this ferry:

Wagon and 2 draft animals, $4.00. ($60

today)

Additional team of 2 draft animals, $1.00.

($15 today)

Carriage with 1 draft animal, $3.00. ($45

today)

One “beast of burden, $1.00.

One horse or mule with rider, $1.00.

One “footman” (meaning somebody walking), $0.50 ($7.50 today)

Cattle and horses, per head, $0.50

Sheep, goat or hog per head. $0.25. ($3.75

today)

|

Ferry

similar to ones used by the Bradshaw's. Courtesy

Mohave Museum of History and Arts, Kingman, AZ |

1926 Ehrenberg Ferry on the Colorado River at

Blyth, Courtesy

Mohave Museum of History and Arts, Kingman, AZ |

1880 “Official Map

of the Territory of Arizona” showing Bradshaw Ferry and a road near La Paz and

a road/trail going east

Courtesy Mohave

Museum of History and Arts.

Isaac

and William Bradshaw operated their ferry together for about a year. However, in 1863 William left to lead a group

of men into the range (which was later named Bradshaw Mountains) in search of

silver and gold ore, which had been reported in the Weaver Mining District, at

Rich Hill. He was too late to stake a

claim on Rich Hill, and headed on to Turkey Creek. In the fall of 1863 William

did strike gold and a new mining district was named in his honor, and he helped

establish Bradshaw City. William Bradshaw, who was a heavy drinker, returned to

Olive City in late fall a year later, in an attempt to “dry out”. He supposedly

got a bad case of “delirium tremens,” and while suffering “a particularly

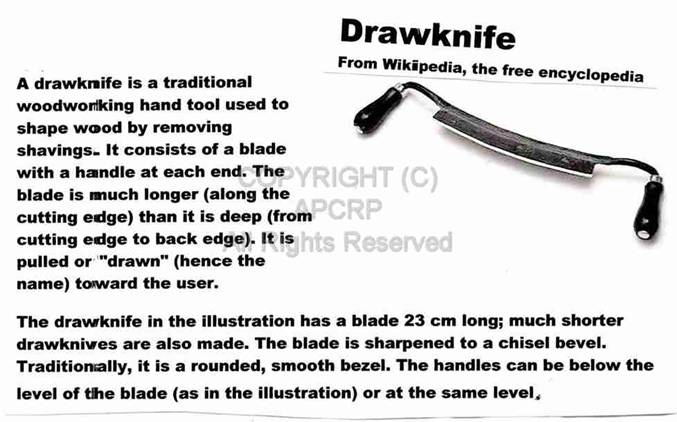

horrible hallucination” slit his throat with a drawknife. He'd walked into a

carpenter's shop, picked up a drawknife, and with one stroke “nearly severed

his head from his shoulders.” He is buried in “an unmarked grave near La Paz.”

(I speculate whether he is buried in the

Ehrenberg Cemetery in

one of the many unknown graves. The historian, Major Horace Bell, commented

about his death: “Alas, poor Bradshaw! A better fellow never lived, and we will

now in charity draw the somber curtain of forgetfulness over his unfortunate

death, which occurred at Bradshaw's ferry on the Colorado River.” Another

historian, Robert Stragnell, in “The History of La Paz” (E Clampus Vitus

Internet site, 1989) wrote: “The most potent character who ever came to Arizona

was John Barleycorn. Came early and long survived and few were the men of that

early day upon whom he did not set his mark. It is not strange that men drank

and gambled almost universally in that time, for human existence was as arid as

surrounding nature, and it was far more pleasant and practicable to irrigate

the human system with alcohol than to bring water to the land.”

There

is some mystery about William Bradshaw's death. He was financially secure and

respected. He had been defeated as a democratic candidate for Delegate to Congress by an overwhelming plurality of 505

to 66, but his opponent was Charles D. Posten. (Later Governor of Arizona.) A

drawknife would most logically be used by an attacker standing behind a victim,

but an unlikely tool for suicide. Generally, both handles would need to be

gripped and the blade drawn towards an object. Bradshaw was very proficient

with the use of firearms, and they were a more commonly used suicide tool!

Also, the only known report was given by James Grant, who had a grudge against

Bradshaw, claiming that he (Grant) was the first discoverer of the Bradshaw

Trail route. No mention of the death is reported in the December 1864

newspaper. The probate of his estate filed in Yuma County listed his death

place as Bradshaw Ferry, Dec. 2, 1864. The original probate papers are missing

and no records of the contents and disposition of his estate are in the probate

record book.

Drawknife.

After

the tragic death of William Bradshaw, his brother Isaac got “gold fever” and

sold his interest in the ferry in 1867. He left his wife and children (who may

have been living in California) and tried prospecting in various areas. He

became a partner in a copper mining operation, but sold his interest in the

Copper Basin property and went to the southern Bradshaw’s. He wasn't very

successful, but made enough “to keep him in beans and bacon.” He died of

pneumonia Christmas Eve in 1885 at his claim in a gulch near Castle Creek,

where he is buried, as mentioned earlier in this article.

The

ferries over the Colorado River between Blythe and La Paz were finally replaced

by a bridge, built in 1928. Photos in the State Archives show a crude span, two

lane, with a dirt road leading to it. Now, a modern freeway bridge (I-10)

crosses at this point, from just south of Ehrenberg, Arizona to Blythe,

California.

In

summary, this article focused on the accomplishments of Isaac and William

Bradshaw and their pioneering efforts to establish the Bradshaw trail to bring

miners and adventurers to the new Territory of Arizona. Their ferry enabled easier travel across the

Colorado River. Their further adventures

to the north and east in Arizona have been described in other

APCRP articles.

Their name lives on in Arizona with the Bradshaw Mountains and Bradshaw

City. In California, remains of the

historic Bradshaw Trail provide backcountry driving recreation.

American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet Publication

Version 061411

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright © 2011 Neal Du

Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS