HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet Presentation

© Copyright 2009 – All rights

reserved.

Version 072609

TALES FROM THE CRYPT

Stories That Death Certificates

Can Tell Us

By Kathy Block

Pioneer Mexicano

Cemetery – Morenci/Stargo, AZ

Photo courtesy: Tom Gilleland

Reading

APCRP research bulletins about grand efforts at

Helvetia Cemetery to research Death Certificates to determine who might be

buried there and at other cemeteries inspired me to use the APCRP web site link for Arizona Death Certificates for

Greenlee County. I was able to eliminate some of the cemeteries listed because

Internet research showed they were still active and/or had lists of internments

posted. Cemeteries eliminated included Clifton, Franklin, Old Morenci Mexicano,

Sheldon, Bunkers, Morenci and Duncan. There are two Duncan cemeteries, not

differentiated on the Death Certificates. There are some cemeteries that seem

to be known by several names, and conflicting numbers of burials listed.

Greenlee

County is located along the Arizona-New Mexico border east of Phoenix. The

County, the 14th in Arizona, was created in 1909 and named for Mason

Greenlee, an early settler in Clifton, the county seat. It was formed from part

of Graham County, which opposed the formation because it would lose

considerable revenue. This came from claims, mines, and large scale copper

mining, which began in 1871. In 1918 most mines were consolidated into the

Arizona Copper Company, which later was taken over by Phelps Dodge Copper

Mining Company, which had developed its own mining and smelting interests in

Morenci. This is a major employer in the

region today. Many of those buried in Greenlee County's cemeteries were

miners. Greenlee is one of only three

counties in Arizona without an Indian Reservation. All but seven percent of the

land is owned by the Forest Service, the BLM, and the State of Arizona!

A

fascinating glimpse of early deaths in this copper mining area began to emerge,

as well as some unsolved mysteries. The records of the “Arizona Territorial

Board of Health” began in 1890 for Graham County and were transferred to

Greenlee County when it became a separate county. The person filling out the

forms had a choice of race of the deceased: White, Black, Mexican, Chinese, and

Indian. Many of the Death Certificates were very incomplete with “unknown”

entries, often for name of parents, place of birth, sometimes birth date. One

male, for parents, had “illegitimate” written in large letters. Many of the

early certificates left the place of burial blank, or it was written in

illegible handwriting. I put these in a file of “unknown” for some future

researcher to use, and sent the files to Neal. Arizona became a state on

February 14, 1912, but the Death Certificates for the rest of 1912 continued to

use a form “Arizona Territorial Board of “Health.” The new form, “Arizona State

Board of Health”, began to be used in 1913.

In the

early 1900s, probably because most of the dead weren't embalmed and needed

quick burials, only a small number of burials were out of the area. One, in

1913, was a Chinese man who died at age 62 from “Chronic opium habit.” His

remains were sent to Hong Kong. It didn't say if his remains were cremated. You

can sense someone holding their nose in this entry: “Was found dead on the

floor of his room. Probably died one month before. Coroner was ill and owing to

decomposition, immediate burial was necessary.” The early death certificates

did not have a space for an embalmer's signature nor for an established funeral

home. Reading thru these Death Certificates is like turning the pages of a

history book to read glimpses of life in a mining area almost 100 years ago.

Demographics

shown in the Death Certificates for the early 1900s revealed about 90 percent

of the burials were Mexican, many from Mexico. One Internet article stated:

“Mexicans were tolerated in most camps and eagerly sought out in some camps

only because, according to a 1900s report, they were considered 'docile, fairly

efficient, and used to low pay at home.'”Morenci is a good example of this

practice.

Mute

evidence of many deaths of young children from diseases such as diphtheria,

typhoid, dysentery, measles, whooping cough, cholera, enterocolitis, and gastroenteritis

were recorded. Some causes could lead to speculations about the circumstances.

A 4 year old boy died of 2nd degree burns on his arms, face, chest

and legs in 1911. An infant died of syphilis, no father. A 6-year-old Mexican

male fell “122 feet in hole.” A 7-month old infant died from “poor hygiene –

put round object in mouth in artificial feeding.” One female newborn was “weak

and funny baby, last born of pair of twin girls.” A 2-year-old girl died from a

scorpion sting. An infant died from “basal fracture of skull-suffocation?

Accidental? “ There were many stillborn children, age listed as “0”. One

stillborn had “ABORTION” written in large letters for cause of death. Doctors

often noted “inanition” (malnutrition). One child was “sick 15 days, wouldn't

eat, no physician.” A 27-day old baby girl died in 1913 from “malnutrition due

to hare lip.” (Treatable today.) Many infant deaths listed no physician. All

this suggests that poor or non-existent medical treatment in that mining era

was possibly contributing to deaths of children and others. Many burials had no

undertaker listed, were they buried by parents or family? One baby, age 1 year,

was “buried at home” near Duncan (clear evidence of the practice) and many

stillborns and infant deaths showed “none” for burial place, others indicated

“home”.

An

Internet article said that during World War I an influenza epidemic claimed

many babies in the Morenci area. Families would take the small victims at night

and bury them in the narrow spaces near graves of kin. Was this possibly to

avoid being quarantined and miss work? I did not notice an increase in infant

deaths on the Death Certificates for this time period; many may have gone

unreported and unrecorded?

Life in

a mining town was often fatal for adults, too.

A big event in Clifton must have been a shoot-out in July, 1911, between

a deputy sheriff and a Mexican. Both died, and their Death Certificates

followed one another. The note for the Mexican stated, “The deceased came to

his death by gunshot inflicted by the deputy sheriff in discharge of duty.” The

sheriff's notice simply said he'd died “by mutual gunshot.” There were murders,

including the deaths of a number of women shot by husbands. There were

suicides, often listed as “self-inflicted gunshot” and “gunshot-suicide.” Both

males and females died from “acute alcoholism” or, as a physician with a sense

of humor, listed several deaths in 1913 as “Over indulgence in alcoholic

stimulants.” Both men and women and babies died from syphilis, for which there

was no cure in 1911. A stockman from Texas was killed by a fall from his horse.

An unusual cause of death was “unbreaking pulmonotis, a broken heart.” The 19

year old Mexican woman had been deserted by her husband and had possible

“hygiene problems.” A single nurse from Canada, no age known, died from

“strychnine poisoning by own hand – unknown whether accidental or suicidal.”

Many

people died in the mines from falls, dynamite explosions, and in one bizarre

accident, a 25-year-old laborer “came to his death by being caught by a set

screw and whirled around shaft.” On

August 13, 1913, a Baby Gauge Locomotive pulling a train used to transport ore

from the Coronado Mine on the terrifyingly steep Coronado Incline failed and 10

people were killed. The incline was 3,300 feet long and 1,500 feet high and ore

was transported to the smelter near Metcalf. The ten Death Certificates, one

after the other, all state, in terse words, “Crushed to death in accident on

the Coronado Incline.” The dead included a mining engineer, machinists,

engineers, helpers, laborers. Some were Italian, some Mexican, some white, and

they were buried in many of the area cemeteries.

Non-miners

were murdered. A 45 year old man from Wisconsin was a “lawyer and picture show

man.” Cause of death “gunshot, died instantly, murder.” A 55 year old Mexican,

described as a “burro wrangler”, was murdered by an unknown party. A barber

died from a “gunshot wound just above the shoulder blade, bleeding to death.”

Other

causes of death included a 37 year old white woman with name, in quotes, as

“Lola Lee”. She was a “sporting woman” and died “taking mercury dichloride

tables, 182 grains each.” (This was used to treat syphilis and had a very small

margin of safety.) A 22 year old “joy lady” died of TB. “Old age”, when there

was much less known about treating the elderly, led to “Died of old age. Was 70

years old.” and for a 100-year-old man, “Chronic vascular lesions – the nature

of which I do not remember, not knowing him for any care.” As now, people have

unusual ways to die, or death finds them in strange ways.

In

Morenci one cemetery was located by the Arizona Central underground mineshaft.

If someone died in the mine, coffins were stored nearby, No embalming was done,

but there was a window in the lid. The family would be called and the custom

was to stand the coffin up so they could have a last photo taken with the

deceased! Supposedly this created a problem once when two men were courting the

same girl, and then she married someone else. The jilted lover committed

suicide and the family wanted the former girlfriend and the other suitor's

photos taken with the deceased. When they stood the coffin up on a chair, it

was knocked over a big wind. The superstition arose that the suicide would never

rest until the other jilted suitor was dead. Is this just a tale or did it

really happen? The records of the time are silent. A cemetery at Metcalf Mine

was moved to Clifton in 1948 and the graveyard at the Arizona Central shaft

(where coffins awaited victims of mining accidents) was moved to East Plant

site in New Morenci in 1951. The Metcalf cemetery lists 709 burials (it's still

active at New Metcalf). Are bodies really there, or were just the headstones

removed, and actual graves buried under tons of slag. A reconstructed list of

burials is on the Internet, from a photograph of the 2-ton monument which had

marked the cemetery and later disappeared.

Some

mysteries emerged from Death Certificate research. The Old Catholic Cemetery,

which has 13 listed burials, also known as Sacred Heart Cemetery, is all that

remains of Old Morenci. The rest of the town was either blasted away in

expansion of the open pit mine or buried under tailings piles. Some burials

went back to 1881; no one has been buried there since the 1930s. In 1983 a

field surveyor for Phelps Dodge stated the cemetery wouldn't be disturbed

because “the surface indicators show there is no mineralization of value

there.” The cemetery was about one mile

from town, and since there were no roads to it, apparently 50 to 60 miners

would line up behind a coffin and take turns carrying it to the cemetery. I

have found burials for the “Catholic Cemetery” listed in Death Certificates for

the early 1900s that do not appear on burial lists on the internet for this

cemetery. Possibly there are two “Catholic cemeteries.”

There

appears a “Morenci Fraternal Cemetery” in many Death Certificates, yet the

Internet lists no names recorded. I have sent files of these burials to Neal. A

query to the local historical society in Clifton is as yet unanswered. I

suspect it was one by the mine shaft. I looked at Death Certificates for 1947,

a year before one cemetery was moved, and among the only 71 death certificates

for that year, none mentioned “Fraternal” cemetery and there were few

Hispanics. An area of future research

will be to look at Death Certificates between 1919 and 1946 to see when the use

of Fraternal Cemetery was stopped. Also, a personal visit to the area may

answer some questions, if the historical museum is open.

The

Find-A-Grave site shows a number of small family cemeteries, possibly on

ranches or homesteads. Some are individual gravesites, such as one for Ike

Clanton of O.K. Corral fame in Tombstone and a woman. The “isolated grave” was

found in 1996 by a descendent of Clanton, who was waging a battle with

Tombstone officials to have these remains, if they are Ike's, reinterred next

to his brother on Boot Hill. Most of

these little cemeteries have no records of who is buried there. However, one

1912 burial in the Death Certificates was a 65 year old Mexican goat herder

from the Nelton Ranch on the Gila River and buried there. He died from

“rheumatism and stomach problems.”

A photo

sent to me, by Tom Gilleland of Tucson, showed a derelict cemetery off Eagle

Creek Road SW of Morenci. It may be the unknown Eagle Creek Road cemetery

mentioned on the Internet. This photo inspired my Greenlee County research.

Historic Pioneer Mexicano

Cemetery – Morenci/Stargo, AZ

Photo courtesy: Tom Gilleland

To

summarize, looking at Death Certificates for Greenlee County provides much of

interest as well as a way to possible locate forgotten, derelict cemeteries.

There is no set year for the research to end. I began in 1888. I continued

until it became apparent that there were no more clues to lost graveyards or

burials, around 1915, though I jumped to 1947 to see if Fraternal Cemetery was

still listed, which is was not. Sometime I will continue research in the years

between 1915 and 1947, to see when the listings for Fraternal Cemetery actually

ceased. The records go from 1844 thru

1958 for some counties, which pretty well covers the

period of early graveyards and cemeteries and their establishment, use, and

possible abandonment, for APCRP members to find

again! Why not consider trying research in an area where you live? Contact Neal

for a very clear, easy to use guide, and you'll be on your way to an adventure

in history and a glimpse of early people who lived, worked, and died as Arizona

evolved from a Territory to a State.

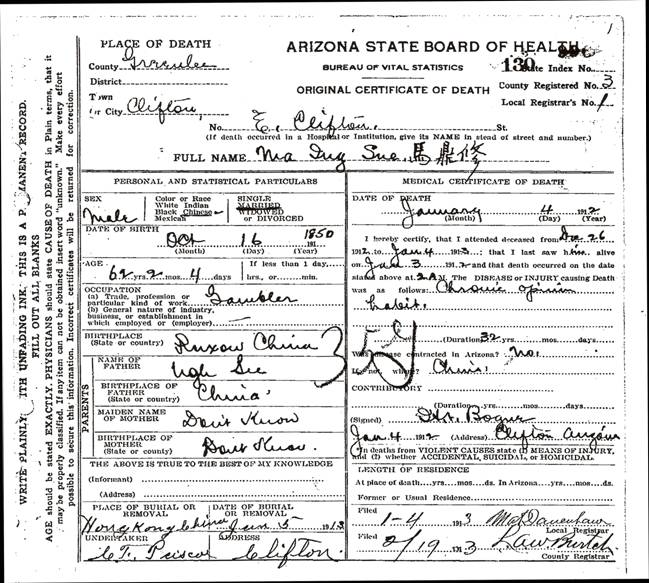

Example of 1912 Arizona Death

Certificate

The

author wishes to thank William R. Halliday, M.D., Retired, for advice on

medical terms and conditions; Tom Gilleland of Tucson for the cemetery photo

that “started it all.” Someday I will find out more about that cemetery, which

is definitely derelict. And, finally, to Neal Du Shane for his patience in

helping me set up Document files, making useful maps, and checking out cemetery

locations and related information. When

a visit can be made to this remote county, possibly I can update this research!

If

anyone has further information on cemeteries in Greenlee County, please contact

me thru APCRP at n.j.dushane@apcrp.org Thank you!!!

American Pioneer

& Cemetery Research

Project

Internet Presentation

Version 072609

WebMaster – Neal Du Shane

Copyright

© 2009 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this

website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS