HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION

| GHOST TOWNS

| HEADSTONE

MINOTTO

| PICTURES

| ROADS

| JACK SWILLING

| TEN DAY TRAMPS

Presentation

Version 090707

Arrastre

and Grave Site in Slim

By: Allan G. Hall

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Click on BLUE text below to go directly to subject)

Historical and Physical Context.

Physical Context of the Arrastre and Cemetery

Survey Techniques Used at the Arrastre

Introduction

If you are not

already familiar with the Monte Cristo and Black Rock Mines near

At the end of this

article you will see map and coordinate data that will aid you in locating the

arrastre and cemetery in

If interested, you

can also read some “high level” information about the “Arrastre” site by

accessing www.wickenburg-az.com, where I have posted some early

findings. The two articles are: “Hard

Way to Make a Living,” and “Hiking Through Legend & History in Middle Slim Jim Creek.”

Historical and Physical Context

The historical

context of any pioneer cemetery is important.

If pioneer settlers died as the result of an encounter with Apaches,

that provides important historical context.

If a miner died from an explosion or cave-in, or in a gun fight, that is

equally important knowledge. In this

case, we have no documented information that can guide us in determining who is

interred at this cemetery, or what led to their deaths. Instead, we are limited to the physical

evidence of the grave sites and the limited historical information about the

mines and trails that existed in the area in the late 1800’s and early 20th

Century.

The arrastre and

cemetery are located just west of the confluence of

The first map

produced by the USGS of this area (1885

The differences

between the 1885 and 1904 maps become important from a research perspective -

particularly with regard to the arrastre and cemetery. The “absence” of a trail on the 1885 map does

not mean it was not there; it may only mean that it was not documented. In contrast, the “presence” of these trails

on the 1904 map (surveyed in 1902-03) confirms that mining-supply routes

existed prior to 1902.

Why is this

important? The ore veins of Black Rock

Mine were not discovered until 1902 and this mine did not commence operation

until 1906. In other words, in 1902 it

was nothing more than a series of claims.

By 1906 it was nothing more than a “prospect” and serious development of

the ore veins did not begin until some time later. Consequently, the Black Rock Mine does not appear

on the 1904 map even though there were important trails in the area.

Similarly, the

Monte Cristo Mine was a more or less “hidden” operation in the years leading up

to 1909. A vein of very rich horn silver

was apparently discovered and mined by Mexican nationals over a number of years

prior to 1904, possibly dating back to the 1870’s. In any case, they made efforts to disguise

their operations and to conceal the entrance to the silver vein. The original miners were eventually run off

by claim jumpers. It was not until 1909

that Frank Crampton rediscovered the carefully hidden ore vein. (See Reference 1)

As you hike around

the arrastre area you will quickly confirm that it could not be seen from the

Monte Cristo or Black Rock Mines, nor was it visible from the very old pack

trails that lead in an eastward direction over the mountain toward the Gold Bar

Mine. This would seem to indicate that

the arrastre was as well hidden from view as the entrance to the silver vein at

the Monte Cristo – perhaps for the same reason.

Neal Du Shane and

I originally named this cemetery site “Black Rock 1” because of its proximity

to the Black Rock Mine and a trail (probably more modern) that connects these

two locations in a rough way. However,

given the historical context that I have provided in the above paragraphs, I am

inclined to drop the term “Black Rock” and simply identify this site as “Slim

Jim Creek Arrastre & Cemetery”. The

reasons for this will become more apparent as the article proceeds.

Physical Context of the Arrastre and

Cemetery

The

arrastre/cemetery is located on the north side of

The area is rather

densely covered with mesquite, Palo Verde and other desert vegetation. In fact, it has been necessary to do a rather

substantial amount of clearing to remove brush and prune overhanging tree limbs

(mostly dead), to enable easier movement on the terrace.

The rock wall

forms a terrace that is approximately 46 feet in length with an average depth

of about 14 feet. On the east end of the

terrace (nearest to the confluence of

Photo #1

“The Arrastre”

Arrastres were important

in early mining days for the pulverizing and amalgamation of gold and silver

ore. This arrastre measures 112” by

108”, so it is reasonably close to a circular dimension. Its size suggests that a single drag stone

was used to crush the ore charge.

The photo shows an

outer ring of “wall” stones that is nearly intact. Just above the bottom of the outer ring

(above the blue hip pack) there is a single stone that leans sharply toward the

viewer in the center of the photo. This

is the only remaining stone of the “inner” ring of the arrastre. The width between the “inner” and “outer”

rings matches very closely to the width of the drag stones that are found at

this site. The two “grayish” granite

rocks on the lower right side of the photo (to the right of the canvas bag) are

“floor” stones that have been removed from the arrastre. The ore charge would have been poured on top

of these floor stones; then the drag stone would have been pulled over the ore

to pulverize it before initiating the amalgamation process. Beyond the

There is no

question that the terrace wall is the reason why the arrastre and graves have

survived to present time. Otherwise,

heavy storm runoff through the creek would probably have destroyed any evidence

of this site long ago. The cemetery to

the west of the arrastre terrace has not fared the ravages of

So, what’s wrong

with this photo? For starters, the

arrastre has been partially disassembled.

The interior ring is virtually gone and the outer ring is missing

several stones! Furthermore, there are a

number of floor stones that are sitting outside of the outer ring of the

arrastre.

I can’t imagine

that anyone would have cannibalized a functioning arrastre for grave stones

while it was providing value to the miners - that just doesn’t make economic

sense. So, there are two plausible

explanations: The arrastre eventually

served no economic or operational value after more efficient techniques became

available or, the arrastre was abandoned without prior intent. A more speculative way of saying this would

be as follows: The arrastre could have

been abandoned when the Mexican miners were run off or; it was abandoned when

the Mexican miners found a more efficient way to process the silver. For example, they may have started

transporting the high grade ore to a nearby mill site via pack train.

In any case, the

stones from the arrastre were eventually scavenged for grave material as you

will see in the following photos.

Without historical documentation, there is virtually no way to determine

how long the arrastre was in operation, or when that operation actually began.

Incidentally, with

a bit of elevation you can actually see an old trail that leads down the east

side of

The Graves at the Arrastre

In photo #2 you

will see four graves. Each is denoted

with a “red” survey flag. The headstones

are aligned on a south to north axis, so the headstones are on the south side

of the terrace. Each red flag marks the

centerline of the axis of burial. Of the

remaining four graves, two share the south to north axis and two have an

east-west axis. This curious alignment

seems to have been made to maximize space for burials and probably has no other

significance.

On the extreme

left side of this photo is the terrace rock wall that rises from 18” to 24” in

height. This formed the front edge of

the 46’ X 14’ terrace area. Each of the

four headstones that you see on the left in this photo was extracted from the

arrastre and they appear to have been drag stones. Each stone has a characteristic hole that was

drilled into the leading edge of the rock – indicating that it was pulled

around the arrastre to pulverize the ore.

Notice in the

foreground of the photo that there is metal debris. There is a hillside to the right of the photo

and there is strong evidence of a settlement up above (metal debris, nails and

some wood). It is possible that these

old cans “floated” down the hillside during decades of repeated runoff, but I

cannot verify this. I can visualize a

piece of light metal being carried by heavy rains in a down-slope direction. Additional discussion about the settlement

above this site will be provided in a future article.

Toward the right

edge of the photo (generally in line with the third grave) you will see another

red flag. It is partially hidden behind

some brush and cactus. This flag designates

the location of another male grave on the terrace (east-west axis).

If you look at the

area near the top where the

Photo #2

“Main Grave Cluster on Terrace”

All of the graves

at this site appear to be male adult or, in some cases, possibly male

juvenile. I have not yet identified any

infant graves. Photo #3 shows a male

grave that is immediately north of the arrastre. I have designated this as Male Grave #1, and

it is most likely a juvenile. To the

right in this photo you can see the outer ring of the arrastre. There are four interesting features to point

out in to photo:

First, the headstone was extracted from the

floor of the arrastre. Close examination

shows a circular grove pattern in the stone, indicating that the drag stones

and ore were ground in a circular pattern over this floor stone.

Second, the large

rock on the right side of the grave is clearly a drag stone. You can easily see the “bore hole” on the

leading edge of the rock.

Third, slightly

above and right of the headstone, there is another drag rock that was used in

the arrastre. The “bore hole” is on the

opposite site of the rock.

Fourth, with

careful examination you can see a metal nail (pin) directly beneath the red

flag at the grave. I have established a

procedure of inserting a pin in the centerline of the grave axis to denote the

grave. I use 10 inch or 12 inch pins

(available at most hardware stores and Home Depot) to outline the perimeter and

center line of all graves. This helps in

the early stages of site survey.

Above and left of

the headstone there is a path that I have cleared to reach the flat area above

the arrastre. This area contains a

settlement and up to two dozen graves that we are still researching.

Photo #3

“Male Grave – North Edge of Arrastre”

In Photo #4 you

will see another male grave that is just west of the arrastre. There are a number of features about this

grave that are worth mentioning.

First, the headstone was also extracted from the floor of the

arrastre. There are strong circular

grooved patterns on the stone.

Second, the red flag points to another metal pin that indicates the

centerline of the grave.

Third, this grave is most likely an adult male – the length is

close to five feet, which would not be uncommon for the 1870-1910 era.

Fourth, the “vacant” space to the right (west) of this grave may

actually contain another grave.

Photo #4

“Male Grave West of Arrastre”

In photo #5 you

will see a different visual angle of what I call the “main cluster” of graves

at this site.

Notice first that

there are four “headstones” that cover what appear to be three graves. Dowsing strongly indicates there is a grave

to the right of this photo. I suspect

that the headstone placements have been somewhat disturbed over the decades

following these burials. Considering the

weight of the stones, it is unlikely that cattle or other wildlife could

account for this movement. So, it is not

unreasonable to believe that human disturbance has played a role in this odd

alignment.

Notice on the left

grave that there is a metal pin near the center line of the headstone. Again, this depicts the center axis of the

grave. The edge of the rock wall that

forms the terrace is beyond the headstones.

Photo #5

“Main Cluster Alignment”

Except for minor amounts

of metal debris, the arrastre-cemetery area is remarkably clean and

undisturbed, and there are no signs that cattle, deer or javelina have used the

terrace for shade or cover.

Making Sense of a Mystery

It was not

uncommon for a miner to construct an arrastre for the purpose of establishing

the initial value of an ore vein, and this might be tested from time to time to

determine if the vein was beginning to yield more or less ore. However, in the major gold and silver mining

districts of

Judging from the

number of drag stones and deeply grooved floor and ring stones that have been

found in the vicinity of the arrastre, the operations at this site must have

occurred over a lengthy period of time.

In addition to the arrastre stones that were used as grave material on

the terrace, we have found numerous stone artifacts above this site, where

there is evidence of a settlement and additional graves. In this case, “quantity of stone” equates to

“time of operation.”

After what appears

to have been a lengthy period of operation, the arrastre in

I can only

speculate on the following statements, so please do not take them as historical

fact. I can offer no documentation that

supports this hypothesis. Sadly, if

there ever was any documentation of this cemetery, it has not survived to the

present time.

Scenario

One

The cemetery at

the terrace could have been used by the Mexican miners at the Monte Cristo

after they stopped using the arrastre.

Considering the span of years of this silver mining operation, it is

plausible that a number of deaths could have occurred due to accidents, health

issues, or hostile confrontations. It is

also possible that some of these miners (and their families) could have lived

in the small settlement above the arrastre.

Scenario Two

Some (or all) of

the graves that are above the arrastre are Mexican miners and/or their

family members. There was a definite

settlement here and there are approximately two dozen graves that we have found

thus far. If the arrastre had a long

term use, burials would have more than likely occurred at this upper location

during the period before the miners were run off.

Scenario Three

The burials in the

arrastre terrace are individuals who worked at the Black Rock Mine after 1906,

and may possibly include individuals who died while working at the Monte Cristo

Mine after 1909. Although there are two

cemeteries at the Black Rock Mine, I have never found any evidence of graves at

the Monte Cristo, which seems curious.

The Monte Cristo probably operated more than twenty-five years longer

than the Black Rock and its main shaft was 1100 feet deep, with more than two

miles of drifts and crosscuts.

Considering the inherent danger of such activity, it is rather difficult

to believe there were no fatalities.

There is no real

way to know. The fact is, there was an

arrastre and there are graves collocated on this site. The fact is, it

would take only fifteen to twenty minutes to walk from the Monte Cristo Mine to

this location. It also takes only about

fifteen to twenty minutes to walk the distance from the arrastre to the Black

Rock Mine. If these graves are related

to the Black Rock, then they date from 1906 to no later than 1941. On the other hand, if the cemetery is tied to

the Monte Cristo Mine, they could date to a period as early as the 1870’s. So, who knows?

I hope to complete

the survey and documentation efforts on the terrace this fall; then resume

survey work at the settlement and grave clusters on top of the hill above the arrastre.

Survey Techniques Used at the Arrastre

Clearing Brush:

As previously

mentioned, the terrace was very overgrown with brush and tree branches when we

first discovered it in March, 2007. The

only effective way to move about on the terrace was to trim back some of the

brush and limbs. Two very useful tools

came into play in this clearing effort:

a short machete and a collapsible saw.

Another handy implement is a pair of wire cutters that I used to prune

jojoba and other shrubs. These tools are

not heavy and don’t take up much space in a backpack.

Grave Marking:

Neal Du Shane and

I first dowsed the terrace in mid-March, 2007 to initially confirm the presence

of graves. Following that, I probably

invested another three trips to the site that were dedicated to continuous

dowsing of the area, as well as clearing out brush to gain access to graves on

the west end of the terrace. It was only

after I had done repeated dowsing that I really felt comfortable in establishing

perimeters for the graves. The tools that

I use for this purpose are 10” or 12” metal nails. I establish the corners of the grave and also

place a nail at the top end of the grave to mark the center line of the burial.

After the

perimeters have been established I attach a Mylar adhesive label that

identifies the grave. For example, “ARR1

Male” denotes the grave number and sex of the burial at the arrastre. These Mylar strips are very durable and

appear to hold up very well to weather and sunlight. Unlike regular plastic labels, the adhesive

bond will not separate. The device that

I use is made by “Brother” and is battery operated with a regular keyboard for

typing out the information. The Mylar

tape comes on spools. I prepare the

labels at home before going to the site.

The worst day of

work is when you hike in with several dozen nails and a small sledge

hammer. That adds a bit of weight to the

backpack and takes up a lot of space.

(Hmmm – water or nails?)

Setting Survey Grids:

In areas where the

distribution and orientation of graves is much more complex than the arrastre

site, my son and I have established a “low budget” surveying method that relies

upon simple geometry, a long tape measure and a good compass. This does require two people, since you can’t

be on both ends of the tape at the same time.

We set nail corners on 10’ X 10’ grids and connect them with sturdy

twine. This has proved to be very

beneficial for mapping and helps us understand how graves are organized. We are currently using this technique above

the arrastre where there are approximately two dozen individual and clustered

graves in a widely dispersed area. If

you are interested in learning more about this technique, please drop a note to

Neal or me. My email address is: allan.hall@mindspring.com.

How to Get There

All

coordinates are listed in 1927 North American Datum, (NAD27), which appears on

the USGS Morgan Butte Quadrangle.

1. Distance from the Wickenburg Rodeo

Grounds to the lower

2. Lower turnoff from

Turn left at 34o 03’ 54”N by 112 o

35’ 04” W - Morgan Butte Grid #4

3. Lower entrance to

Turn right at 34 o 04’ 26”N by 112 o

35’ 22”W – Morgan Butte Grid #32

Elevation is approximately 3040 ft.

4. Arrastre and grave site in

North side of creek at 34 o 04’ 16.5”N by 112

o 35’ 04.3”W – Morgan Butte Grid #33

Elevation is approximately 3161 ft.

5. “Upper” turnoff to

Turn left at 34o 04’ 12”N by 112o 34’

35”W – Morgan Butte Grid #4

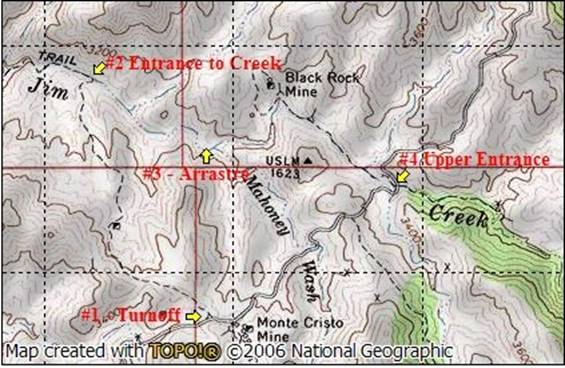

Map

to Arrastre & Graves

Access to the

arrastre and graves is best achieved by turning left onto the trail marked “#1”

on the map. This trail connects with

The upper

entrance, marked “#4” on the map is an alternative way to reach the

arrastre. I recommend that you park your

vehicle in the creek bed below the mine and continue on foot down

This is an active

grazing area for the Williams Ranch, which is located at the end of

There is a rough

trail that connects the Black Rock Mine to the settlement above the arrastre,

but it should not be used by vehicles.

There are several areas of very loose and soft rock that makes this

trail unsafe. Additionally, there is a

water line on this trail that runs from a spring to a watering trough for

cattle. This water line can be easily

damaged and you could loose rear traction if your tires pass over the

line. The trail is also littered with

nails in the area near the mine.

See my article

titled “Hiking Through Legend and History in

Safety Considerations

1.

The

most comfortable time of the year to visit the arrastre and grave sites is from

October through May.

2.

Expect

to see snakes from March through October – Be alert!

3.

Heavy

runoff from the upstream watershed can turn

4.

Carry

plenty of water and energy snacks and, please - pack out your trash.

Reference

1.

Deep

Enough, by Frank A. Crampton.

APCRP Internet Presentation

Version 090707

All Rights Reserved

WebMaster:

Neal Du Shane

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION

| GHOST TOWNS

| HEADSTONE

MINOTTO

| PICTURES

| ROADS

| JACK SWILLING

| TEN DAY TRAMPS