HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet presentation

Version 123011

DOME CEMETERY AND GILA CITY

UPDATED INFORMATION

By Kathy Block

ACPRP Historian

Map showing location of

Dome and probable Gila City.

Since the original article on Dome

Cemetery was posted in 2009, new information has been found about Dome Cemetery

and Gila City. Consequently, this new research about the area should be viewed

as more historically accurate. Personally, it's somewhat embarrassing for one's

research to prove either inaccurate or incomplete. This revised article hopes

to correct some errors and omissions from the original.

The REAL Dome Cemetery is located in a

gulch west of the ruins of Dome. Because

it is primarily a Native American Cemetery, its exact location is not shown,

nor is it open to the public. It's on

property owned by the Tohono O'odham tribe and most of the people buried there

are Hia-Ced O'Odham (Sand People). The Tribe plans to restore this site. Please do not trespass. The small archeological site pictured in the

original article is NOT the Dome Cemetery, nor is it related to any events in

Dome. BLM erected the fence to protect

it from ATV damage.

The roster reflects 34 known burials

at Dome Cemetery, as determined by death certificates and the few markers with

names. There are at least 67 graves spread out along the bottom of a gulch and

onto the bank. Many are marked with piles of stones. Some have remnants of

wooden crosses. There are also a few beloved pets buried nearby. According to a

personal communication to Neal Du Shane, most

Anglo American people who were miners, or who died in the Gila City/Dome area were

buried in the Yuma Cemetery. Those

Native American and Mexican miners who were poor were buried at Dome. Only three could afford grave markers, two of

the memorials for Hispanic miners are pictured here, with translations of the

inscriptions. Note: These photos were taken a number of years before we learned

of the history of this cemetery. At that time, no signs, fences, or caretaker

were evident, and well-used ATV trails led to the site.

|

Figure 1 |

Figure2 |

|

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

Figure 1.

Grave of Antonia Casias. Inscription says:”Baby girl Antonia Casias, born July

5, 1943 and died April 23, 1944, at the age of nine months. Her father and

mother dedicate this humble remembrance to her.”

Figure 2.

Note coins on grave of Concepcion Mendez. Inscription says: “THE BOY CONCEPCION

MENDEZ BORN Dec.7, 1923 DIED June 8, 1924. MY SON GOD'S WILL HAS

BEEN DONE. YET YOU LIVE ETERNALLY IN THE

HEART OF YOUR PARENTS LEO VIGILDO AND CONCEPCION MENDEZ.”

Figure 3.

Grave of a pet.

Figure 4.

Overview of cemetery, looking north.

APCRP was contacted by a person

wishing to add a possible name to the roster and post the roster on Find-A-Grave,

giving credit to APCRP. Historical

information on Find A Grave about the Dome area that mentioned an 1858

“Swiveler's Station” on the short-lived Butterfield Overland Mail route led to

new research findings. This new information was also mentioned in an article

about Dome on Wikipedia.

The name of Private Francisco Salazar

was added in August 2011 to the Dome roster on Find-A-Grave. He was with

Company B, l st Battalion, Native California Cavalry. He had enlisted as a private in Placerville,

California on March 11, 1864. During the march from Drum Barracks to Tucson, he

died of disease at Gila City on August 8, 1865. However, his remains may have

been moved to the post cemetery at Fort Yuma, but there is no record. (See

later note about Fort Yuma.)

The ghost town sites of Gila City and

Dome have little, if anything, remaining. Gila City site is mainly a marshy

curve between the road east and the Wellton - Mohawk Canal to the north. No

visible remains can be seen. Dome ghost town site is now posted as private

land, with trailers occupying the area. It was essentially abandoned by 1940. There

are a few adobe columns and scattered concrete foundations from the train

siding.

Present

day site of Dome

Do not trespass

These areas can be reached most easily

by following the remaining route of the old Butterfield Stage Overland Mail

Route, from Highway 95. Turn east just south of mile marker post/marker number 38,

on a dirt road that travels along the south edge of the Wellton - Mohawk Canal.

The road starts immediately after the highway crosses the canal, driving south.

It is about 5 miles east from Highway 95 to the site of Dome (elevation 194 feet).

The Wellton - Mohawk Canal may have

buried most or all traces of Gila City.

The canal was started in 1949 and finished in 1952. It brings water

uphill from the Colorado River, which was diverted at Imperial Dam into the

Gila Canal. It irrigates 58,200 acres in

the valley and 4,550 acres on a mesa.

Gila City site is a few miles west of

Dome, marked by a delta to your left (north) and a pronounced “U” curve of the

railroad on your right (south). Only a few rusting pieces of metal, bits of glass,

and trash could be found. There was an old well or cistern, but it may be from

a more recent time. The delta area floods

regularly, creating a marshy, brushy barrier to explorations.

|

Figure 6 |

Figure 7 |

Figure 8 |

|

Figure 9 |

Figure 10 |

Figure 11 |

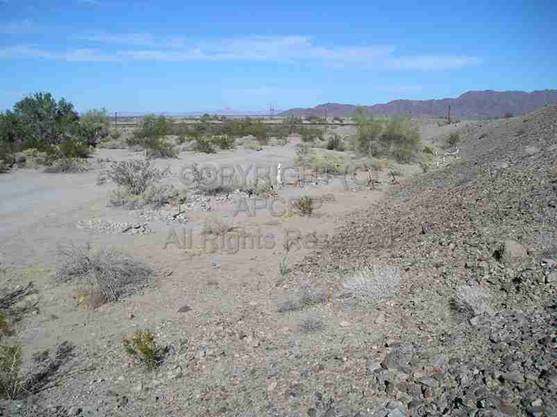

Figure 6.

Looking down on possible Gila City site towards canal .

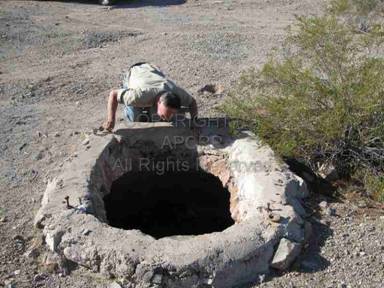

Figure 7.

Remains of old road to Dome.

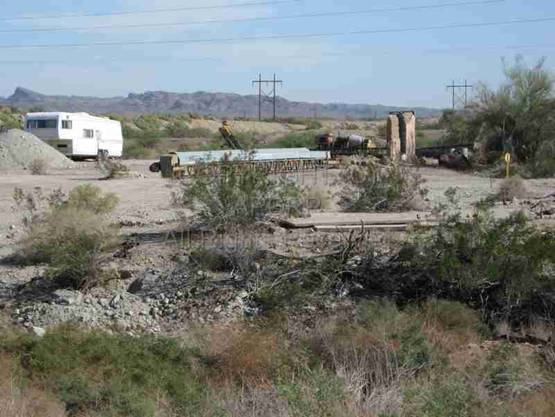

Figure 8.

Present day road to Dome.

Figure 9.

Railroad curves here, probably to stay on high ground.

Figure 10.

Ed Block at old well or cistern. May be modern?

Figure 11. Brushy

barriers to exploration.

If one continues farther east, there

is a rickety wooden bridge over the canal, leading to a series of minimal dirt

tracks along the north side of the canal, past the swampy Gila River and

marginal truck farms. It is somewhat difficult to return to Highway 95 from

this area. It is better to return west to Highway 95 from the Dome area.

BRIEF HISTORY OF GILA

CITY AND DOME

UPDATED

INFORMATION

The history of this area reflects the

discovery of rich gold placers in and around Monitor Gulch, which emerges from

the Gila Mountains to the south. There are two different stories of their

discovery involving a colorful Texan named Colonel Jacob Snively. In 1858 he

led a party of prospectors to this area, which is

about 20 miles east of Yuma and the junction of the Gila River with the

Colorado River. One account claims Henry Birch, a member of the group,

discovered a nugget there near the Gila River. The other account says that

Colonel Snively was given credit as the leader, and reportedly “swished the

water from the Gila River in his pan and saw gold nuggets glittering in the

sun!”

A note about Colonel Snively: He was a

veteran of the Texas War of Independence and had been Personal Secretary of

General Sam Houston. After further adventures, he met a sad end. In 1871 he was shot off his horse during an

Apache attack at White Picacho Mountain.

Wounded and abandoned by his companions, he was captured and tortured to

death. A few days later his old friend

Jack Swilling, part of his original party, returned to the site to bury the

remains. Seven years later Jack Swilling

felt haunted by thoughts of the hasty burial.

Jack traveled to White Picacho Mountain to claim the remains for

reburial in the backyard of Swilling's Stone House in Black Canyon City. While in this process, a stage was robbed and

Swilling was blamed. After Jack Swilling died in the Yuma County jail awaiting

trial, the actual hold-up men were identified, and Swilling's innocence was

established too late.

A comprehensive article on an APCRP

project to erect a monument at the graves of Jacob Snively and Jack Swilling

can be found on APCRP.

http://www.apcrp.org/SWILLING_Jack.htm

Back to Gila City! Gila City emerged

overnight as eager prospectors rushed to the site. These placers were worked

for eight years by thousands of miners.

They worked the plateaus and canyons using everything from skillets to

wash pans. They were panning out $20 to

$125 a day in gold dust, and nuggets weighing up to 22 ounces each were

deposited at the Wells Fargo office in Los Angeles. Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry,

an early adventurer, found about 100 men and several families working the

gravels at Gila City and saw more than $20 washed from 8 shovelfuls of dirt – a

small fortune in 1859. Some miners were paid $3 a day plus board to work lower

grade deposits.

In 1864 J. Ross Browne wrote: “There

was everything in Gila City except a church and a jail which were accounted

barbarisms by the mass of the population. When the city was built, bar rooms

and billiard saloons opened, Monte tables were established and all

accommodations for civilized society placed upon a firm basis. The gold placers

gave out and the remains were washed away by a flood in 1862. All that remains

of the metropolis of Arizona consisted of 3 chimneys and a coyote.”

Any miners who died in Gila City may

have been buried in the historic pioneer cemetery in Yuma or elsewhere, as the

earliest RECORDED burials at Dome Cemetery are 1912. However, some of the

unknown graves could be from this early period of time of the 1860s.

A post office was established first at

Gila City in 1858. This post office closed July 14, 1863, after most of the

town was devastated from the flood in early 1862, and then abandoned for the La

Paz gold rush along the Colorado River. Later post offices were opened in

nearby Dome in 1892, when large scale mining of the placers began with the

coming of the railroad, but opened and closed several times before final

closure in 1940. Various shafts and diggings from mining efforts can still be

found in gulches and plateaus leading down from the north side of the Gila

Mountains.

|

Figure 12 |

Figure 13 |

Figure 12. Dangerous, open shaft.

Figure 13.

Remains of mining efforts looking south towards Gila Mountains.

Another development bringing growth to

the area was the Butterfield Overland Mail Route. It ran west to east between

the Gila River to the north and the Gila Mountains to the south. The present

dirt road east to Dome along the Wellton - Mohawk Canal to the north and the

railroad to the south follows this historic route.

The increasing desire for

establishment of a “regular” transportation system to facilitate the movement

of mail, supplies and people arose with the movement of people to the southwest

to prospect and settle. In 1857 Congress voted to subsidize a semi-weekly

overland mail service from “some point of the Mississippi River as the

contractors may select, to San Francisco.” The distance each way had to be

traveled in 25 days or less. Service had to begin within 12 months after the

signing of the contract.

In 1858 John Butterfield, born in 1801

near Utica, New York, and a former stage driver in the East, won a government

contract of $600,000 a year for six years to carry mail from St. Louis to San

Francisco twice a week. Butterfield

spent more than one million dollars to start his company! His “Butterfield

Line” became the “Overland Mail Company”. The large, high quality coaches were

manufactured in Concord, New Hampshire, weighed 2,500 pounds, and cost roughly

$1,300 each.

There were 139 relay stations and

forts, 1000 horses, 900 mules, and 250 Concord and Celerity Overland Stage

Coaches used by some 800 men employed by Butterfield. Many of his men were old

and experienced frontiersmen who often were friendly with various Indian tribes

along the way. He supposedly told his drivers, “Remember boys, nothing on God's

earth must stop the mail!”

Butterfield refused to carry gold or silver in

an effort to cut down on attacks by highwaymen. At first he carried only

letters, but later began to transport newspapers and small packages. Freight

and goods that people wanted were bulky and often ordered in quantity, so they

were transported in freight wagons, not stagecoaches, and at a much slower

pace. The first westbound stage arrived in San Francisco one day ahead of

schedule on October 10, 1858.

In Mark Twain's book, “Roughing It”,

he humorously described his coach and travel conditions in “Travel on the

Overland Stage, July-August, 1861”: (The full text can be read by checking: http://www.mindspring.com/~eliasen/twain/roughing/roughing.html

“Our coach was a great swinging and

swaying stage, of the most sumptuous description – an imposing cradle on

wheels. It was drawn by six handsome horses, and by the side of the driver sat

the “conductor”, the legitimate captain of the craft.....We (three passengers)

sat on the back seat, inside. Almost all the rest of the coach was full of mail

bags-for we had three days' delayed mails with us....We had twenty-seven

hundred pounds of it abroad. We changed

horses every ten miles, all day long, and fairly flew over the hard, level road. We jumped out and stretched our legs every

time the coach stopped....We stirred up

the hard leather sacks, and the knotty canvas bags of printed matter...and

redisposed them in such a way as to make our bed as level as

possible......(then put on layers of clothes they had taken off during the hot

day)...placed the water canteens and pistols where we could find them in the

dark.....Whenever the stage stopped to change horses, we would wake up, and try

to recollect where we were-and succeed-and in a minute or two the stage would

be off again....!”

Although these coaches were primarily

for mail, they also accepted passengers such as Mark Twain. Passage for the

whole route cost $200, and shorter trips were 15 cents per mile and a passenger

was allowed twenty-five pounds of baggage, two blankets and a canteen. The coaches traveled full speed twenty-four

hours a day, there were no stops for bed and breakfast, only hurried intervals

at the station houses when they changed horses. Most were offered meals of

bread, coffee, cured meat and sometimes beans. Beverage, offered by one station

keeper, was described by Mark Twain as “slumgullion” that “purported to be tea,

but there was too much dish-rag, and sand, and old bacon-rind in it to deceive

the intelligent traveler.” He had no sugar, no milk, not even a spoon to stir

it with! Meals generally cost $1.00 each.

Danger from attacks by Native

Americans (as in the painting below) was high , especially in the Chiricahua

Apache regions in Southern New Mexico and Arizona. (East of Dome). A poster

warned the passengers, who were encouraged to carry firearms (Mark Twain

mentioned his pistol) at the onset of a trip. It said:

YOU WILL BE TRAVELING

THROUGH

INDIAN COUNTRY AND THE

SAFETY

OF YOUR PERSON CANNOT BE

VOUSAFED BY ANYONE BUT

GOD.

The stations were typically long, low

huts, made of adobe bricks, laid up without mortar. They had barns, stables,

and a hut for an eating room for passengers. The hut had bunks in it for the station

keeper and his helpers. Most had no windows, but a square hole without glass to

enter. There was a packed dirt floor,

often a fireplace but no stove, no shelves, no cupboards, and no closets. A

stone corral had portholes in every stall, and firearms and ammunition were

stored in case of Native American attacks.

The Overland Stage Coaches passed thru

southeast Arizona twice a week, on Sundays and Wednesdays.

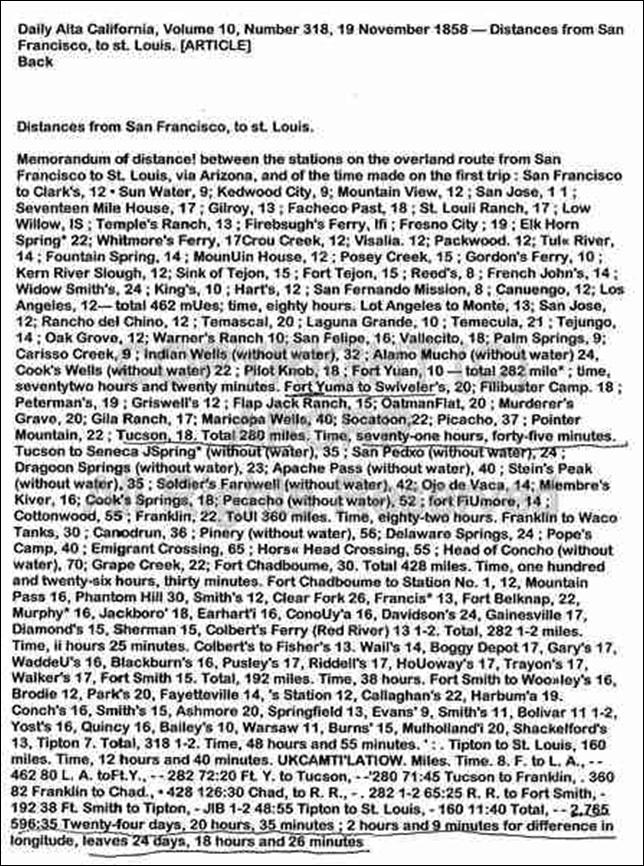

An announcement in the “Daily Alta

California” newspaper, Vol.10, No.318, 19 November 1858 gave details of the

route thru the Gila City area. At the

time, it was called “Swiveler's. There was also a “Swiveler's Ranch.” The route

from San Francisco to St. Louis was a total of 2,765 miles. The company

calculated the trip to take “24 days, 20 hours, 35 minutes; 2 hours and 9

minutes for difference in longitude, leaves 24 days, 18 hours, and 26 minutes.”

After crossing the Colorado River on a ferry, Fort Yuma to Swiveler's was 20

miles; next stop, Filibuster Camp, 18 miles. Total on to Tucson was 280 miles,

with a travel time of seventy-one hours, forty-five minutes. The stagecoaches averaged 5 to 9 miles per

hour. When the trail became very rough, the passengers had to switch to a more

uncomfortable but rugged “Celerity” stagecoach. This was known as the longest

stage line in the world!

John

Butterfield ran up large debts with The Wells Fargo Company despite the

$600,000 yearly grant awarded from Congress. In March, 1860, he was forced out

and Wells Fargo took over the stage route. Butterfield, age 59, retired to his

home near Utica, New York, and died at age 68 from a paralyzing stroke in 1869.

John

Butterfield ran up large debts with The Wells Fargo Company despite the

$600,000 yearly grant awarded from Congress. In March, 1860, he was forced out

and Wells Fargo took over the stage route. Butterfield, age 59, retired to his

home near Utica, New York, and died at age 68 from a paralyzing stroke in 1869.

The Butterfield Stage terminated

operations on March 30, 1861 along this southern route at the outbreak of the

Civil War. Texas seceded from the union early in 1861, and the Overland Mail

left the southwest. The contract was rewritten by officials in Washington so

that the mail could travel thru Nebraska and Utah. This was a devastating blow to the settlers

and miners in the New Mexico Territory, which included all of present-day

Arizona. Some of the stock and property were confiscated by the Confederates,

and the military could no longer protect travelers. Remaining animals and

property were moved to California. A reporter named Thompson Turner predicted

this would be a “death blow to Arizona.” He wrote:

“The prospect of a withdrawal of the

Overland Mail from this route has

caused

a complete stagnation in business and enterprise. 'What will we do?

Where shall we go?' is in every man's

mouth...Private letters from

Washington State that it is even in

contemplation by the new Administration

to

withdraw the troops from this country.

If this should be done, we are ruined

and Arizona will lapse into nothingness.”

The old Butterfield Road was used by

both the Confederate and Union armies, and Arizona was virtually cut off from

communication with “the outside world.”

The next public mail to reach Tucson

from California came on horseback September 1, 1865, although the Pony Express

operated for a few years on a northern route, until the completion of the

transcontinental telegraph line in 1861. The first mail from the east arrived

August 25, 1866, but it wasn't until the coming of more miners and the

railroads in the 1870s and 1880s that regular contact with the States was

restored!

An interesting account of conditions

at Gila City in 1877 by E. Conklin called “Picturesque Arizona: Being the

results of travels and observations in Arizona during the fall and winter of

1877” describes a hotel there 15 years after the flood of 1862. The writer, who

was a member of an ambulance corps and commissary depot traveling east from

Yuma towards the Santa Rita Mountains, described what remained of Gila City.

“The remnants of an ambition often revived, and as often overthrown, a living

skeleton of a miner's hope and fancy, and the scene evidently, in days gone by,

of all the vicissitudes of a miner's and prospector's life on the borders of

our country. In 1861 the population of this city numbered about twelve hundred

persons.” When Conklin stayed overnight, there were only 6 people total living

there, running a primitive “Gila Hotel”. He later commented, “Nothing exciting

disturbed the quiet of the place at the time of our visit. Only one man had

been shot the day before one arrived, and the perpetrator was then off in the

mountains, looking for more gold heaps.” (No indication where the murdered man

was buried.)

The remains of Gila City died out in

the early 1870s, but the area came back to life again as a rail siding named

Dome, a mile or two east of Gila City.

The Dome post office was established in 1892, and the town's residents

enjoyed mail service under the city names of Dome, Gila, and Monitor during the

periods that the town had mail service..

The railroads arrived to the Gila

City/Dome area in November 1878. The Southern Pacific Railroad hired about

1,100 Chinese workers and 200 Anglo construction workers to lay track at the

rate of more than one mile a day. The Chinese were paid $1 to $3 a day. They

were at first thought to be too weak or frail. Workers from China received less

pay and eventually went on strike and got small increases in wages. They

reached Gila Bend by April, 1879. Work

was suspended during June and July and Chinese workers either shipped back to

California or stayed in Arizona to work in the mines. Some may have worked

placers at Gila City?

Construction resumed in January 1880, and on

March 20, 1880, the Southern Pacific train arrived in Tucson. There were many

conflicts and problems in the construction of the railroad, beginning with

quarrels over building a bridge over the Colorado. The small Yuma garrison had

orders, to be carried out by a Major Tom Dunn, to prevent the laying of any

track on a bridge built in 1877 by the Chinese workers, but the track was

completed despite his resistance (which included bravely facing an oncoming steam

engine until he and his men were forced to retreat) and the trains rolled on

east!

Fort Yuma was actually on the

California side of the Colorado River from Yuma, Arizona. It was on the

Butterfield Overland mail route from 1858 until 1861. Fort Yuma was abandoned

May 16, 1883. The Quartermaster Depot was on the Arizona side of the river

between 1864 and 1891, and provided military supplies and personnel to posts

throughout Arizona and New Mexico. The soldier mentioned earlier as possibly

buried in Dome Cemetery probably came from this facility or Fort Yuma.

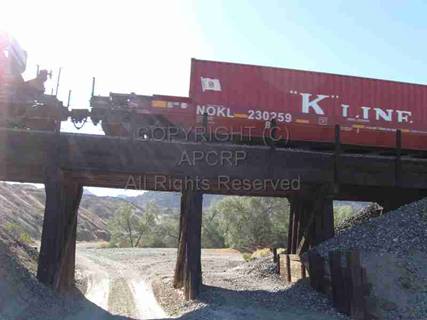

Today, a busy train line parallels the

old Butterfield Road, with trains roaring by the sites of Gila City and Dome.

Train

crosses over underpass that leads to a gulch

where Gila City miners may have worked the

placers.

Only a cluster of trailers remains at

the mouth of a gulch near the site of Gila City. This is all private property. Dome is all

private property, also. A person wishing to see the remnants of these historic

mining areas is advised to stay on the public road. There are underpasses to

the south, however, with primitive, sometimes flooded, roads that lead to an

old pit mine called Grey Fox Mine, open shafts, and other evidence of the

prospectors and their efforts in the mid-1800’s and on into modern times. If

you explore this back country, think of the miners and prospectors who once

worked this area and the brief boom towns of Dome and Gila City! Many of these

people may remain in the Dome Cemetery, in unknown and unmarked graves.

Enclave

near Monitor Gulch, west of Dome.

Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet presentation

Version 123011

WebMaster:

Neal Du Shane

Copyright

© 2011 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website

may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for

financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the

Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS