HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 033009-2

Dry Stack Walls – A Pioneer Legacy

The first article on Dry Stack Walls provided a brief history about the

development of mining in the Arizona Territory and a discussion of stage coach

and freight roads that utilized dry stacks to provide durable transportation

routes to the interior mining districts.

Part Two combines additional photos with interpretive text to explain

how pack trails were constructed.

Part Two: Mine

Trail Construction

This article - Part Two - deals with the smaller (less well constructed) trails that connected between major roads and mines of the pioneer era. Based upon my observations I am compelled to characterize “Mine (Pack) Trails” as narrow routes that were suitable for horses and pack animals (mules and donkeys) and were, at best, able to accommodate wagons on a single path. In most of the examples I have studied however, even the use of small wagons would have been either highly tedious or completely impractical on these trails.

Owing to their narrower construction, and the fact that they hugged the mountainsides, pack trails are more difficult to spot. As with old stage coach roads, time and the weather have reclaimed some of them. Nevertheless, dry stack wall construction provides an opportunity for discovery. This is particularly true in mountainous locations where runoff posed a risk. All you have to do is study the terrain and understand where trails might have crossed hillside gulches.

Figure 1, Ammil-Ambest Pack Trail

The Ammil-Ambest pack trail (Figure 1), which is located in

the Hassayampa River Wilderness Area (in the northerly direction toward Wade’s

Notice that the wall was constructed using “native” stone. There is no evidence that any of these rocks were shaped by stone masons, (in contrast to the stage and freight road walls shown in Part One). I would characterize this as a reinforced stacked wall. The integrity of the trail at this crossing is still very good.

The wall and trail also confirms an economic fact about the Ammil-Ambest group of mines. That is, the mineral content was not of sufficient value to warrant the development of a more substantial road. Had the circumstances been otherwise, the mine group might have had an on-site mill and the heavy equipment needed to process high grade ore. Under these circumstances the “trail” would have become “road” that would have been wider to support heavier traffic.

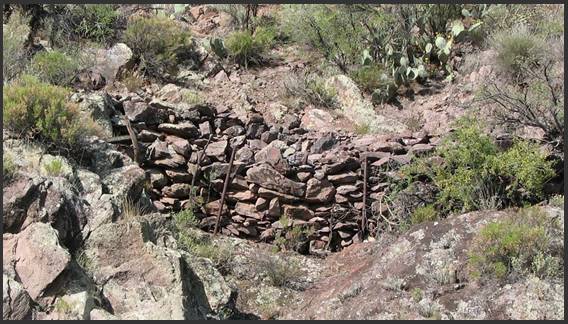

Figure 2, Typical Pack Trail Dry Stack

Figure 2 is an example of a dry stack along a steep hillside in the Black Rock Mining District. In this case, the wall provides a level road (laterally) for a short distance before reaching the top of a hill. The dry stack was not constructed to address runoff from natural gullies (as compared to Figure 6). Trail and wall construction is very crude, but survives to this day. The trail is almost indiscernible at the base of the hill (lower left), where it rise from a creek bed, and at the top (upper right), where it crests at the top of the hill. Trees and desert brush have overtaken most of this trail and the roadway is in poor condition along the dry stack. I would surmise that the relatively “loose” construction of the wall has allowed runoff to seep through the stones and accelerate erosion.

I have found many dry stack walls like this rising from a wash or creek. This particular pack trail is estimated to be about 140 years old. Although the trail surface is eroded and overgrown with desert plants, the wall still serves as an excellent clue to nearby mining activity and pioneer settlements.

Figure 3, Dry Stack Pack Trail in Slim

Figure 3 provides another example of a dry stack wall on a pack trail to a mine. This particular wall is so crude and fragile that you almost have to wonder how it served its purpose! I can only conclude that it was not intended to support any traffic other than the four legged variety. The approach to this trail (right and below of photo) is entirely washed out, but the surface above the dry stack remains in relatively good condition. There are two other prospect adits within 50 yards of this photo.

As previously noted, many trails (and even stage coach roads) utilized the broad and sandy expanse of washes and creeks whenever possible. However, when you travel through the mountainous areas, the rapid change in elevation and frequent granitic extrusions created obstacles to pack trains and wagons. In such cases it was necessary to construct “bypass” trails.

Figure 4, Bypass Pack Trail

Figure 4 shows a particularly steep trail which bypasses a fifteen-foot high granite dike. I have often wondered about the limits of freight loads that could be safely transported along this trail. The angle of ascent at the lower left of the photo would require low-range four wheel drive in modern times. Imagine what a freight wagon driver would have thought while hauling a heavy load on this trail! The approaches to both ends of the bypass were washed out many years ago, but the dry stack wall and roadway remain in reasonably good condition. There are many instances of bypass trails in the mining districts, where trails were cut around obstacles in creeks and washes.

This trail leads generally east toward the Black Rock, Gold

Bar and George Washington mines and probably dates to the 1870’s. There are also pack trails leading north (right

and downstream) toward the terminus of

One of my favorite observational activities is to search for old pack trails. Major roadways are not particularly interesting to me because they are more heavily travelled and do not necessarily follow the routes that were established during the pioneer mining era. Locating pioneer era pack trails almost always entails long range scanning from hillsides.

Figure 5, Pack Trail near George Washington Mine

Figure 5 shows a trail that I have highlighted with red lines. This image shows two pack trails that lead from left (south) to right (north) toward a mine. The upper trail shows a dry stack wall (right of center in the red oval) that crosses a gulch on the hillside. If you look carefully, there are actually two more trails in the photo. Features such as this – even at a distance – are important indicators of routes to old mines. The ore vein at the nearby mine was originally located in 1880, but was not worked continuously. It was “rediscovered” in 1924 and a more modern road was cut along the mountainside behind this photo perspective.

Many mountainsides – particularly if they overlook a basin – can yield a dozen or more old pack trails.

What Do These Photos Tell You?

1. Each of the photos in Figures 6 through 10 was either shot at an angle looking “up” at a hillside or “across” a gulch or canyon. In other words, you must be aware of your surroundings above and across your area of transit. I cannot begin to tell you how many times I have missed seeing a pioneer structure when passing through a creek or gulch for the first time.

2. The hillside approaches to old pack trails that climbed out of creeks or washes may have been eroded by runoff, making it difficult to easily detect them. Again, you should look “up” as you hike through any area to see if there are dry stack walls.

3. Identification of trails frequently depends upon favorable lighting conditions. The photo in Figure 10 was taken in the morning hours looking west. This trail is not visible in the late afternoon when the mountainside is covered in shadow.

4. Position your search for pack trails based upon time of day. Look west and south in the early morning and look east and north in the late afternoon. Gaining elevation on hillsides and mountain saddles can provide several square miles of search area.

5. If you are actively searching for pioneer sites, take your time! Whether you are on foot or in a vehicle, stop frequently to examine your surroundings. When I say “frequently”, I mean that you should thoroughly examine your surroundings at least every 100 to 200 yards. Taking the time to observe the terrain from different angles will frequently reveal old trails. The history is already there – your discovery depends upon your patient observation. There are two tools that you can use to aid your discovery efforts:

a. Old USGS and mining district maps. And, I do mean OLD. I have USGS maps that date to 1902, 1929 and the 1950’s that reveal trails that are not shown on more recent map publications. You can contact the USGS to ask for color photo-prints of these old maps if you are so inclined.

b. Old aerial photographs. There are two advantages to these photos: First, old photos show routes and trails at a point in time when they were less affected by erosion and plant growth. Second, old photos do not show more recent (illegal) trails that have been created by off-road vehicles.

Both research approaches (old maps and aerial photos) require patience and a commitment to studying the topology and features of the area that interests you. If you have the time, this is a great way to refine your focus.

In Part Three of this series we will examine a variety of dry stack

walls that can be observed at old mines and settlements. Examples will include heavy walls for ore

dumps, terraces and foundation walls.

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 033009-2

Copyright © 2009 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be

used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of

any kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer &

Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS