Americn

Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project

Internet Presentation

Revised 042020

Second Edition

By:

Kathy Block

APCRP

Research Staff

|

Location of Harshaw’s Two Cemeteries, Courtesy Neal Du Shane |

Accounts of Spanish missionaries

traveling through the area shortly after the founding of Tubac state that the

site, that was to become Harshaw was originally a Spanish settlement and ranch.

The settlement was known as Durazno, meaning "peach" or "peach

orchard," supposedly due to the peach trees which had been planted there

at some time in the past. According to a missionary account from 1764, the

settlement of Durazno was attacked and destroyed by Apache Indians on February

19, 1743, with significant loss of life. Along with the nearby Salazar ranch,

which was also attacked on that day, the lives of 44 residents were lost.

When the United States acquired all of

present-day Arizona as part of the Gadsden

Purchase in 1853, the numerous Mexican mining and ranching

settlements still in existence became part of the United States, and American

settlers moved into the area

David Harshaw, stationed at Tucson in the 1860s as a Sergeant

in the First Regiment of Infantry of the California Column. When he left the

army, he returned to his previous occupation of ranching. Harshaw was ordered

off of Apache land by Indian agent Tom Jeffords in early 1873 for illegal

grazing. In order to find new pastures for his cattle, Harshaw settled later

that year in the area that was to become the community which bore is name, which

was known locally as Durazno.

The main Harshaw Cemetery is essentially

a family cemetery maintained by descendants of Angel and Josefa T. Soto, who

settled in the area in the 1880s. Other families, though, have many members

buried there also, mostly residents of Harshaw, which was settled the 1870's. As

written earlier, the original name of the settlement was Durazno which means

"peach" or "peach orchard," supposedly due to the peach

trees which had been planted there at some time in the past.

It was renamed after David Tecumseh Harshaw, who first successfully located

silver in the area.

The Hermosa Mine, a silver mine opened

in 1877, was the foundation for the town's economy. In a four month

period it produced $365,455.00 in silver bullion. At its peak the town had a

population of about 2,000 people; 150 worked at the mine and another 20 at the

stamp mill. Harshaw mines were among Arizona's highest producers of silver.

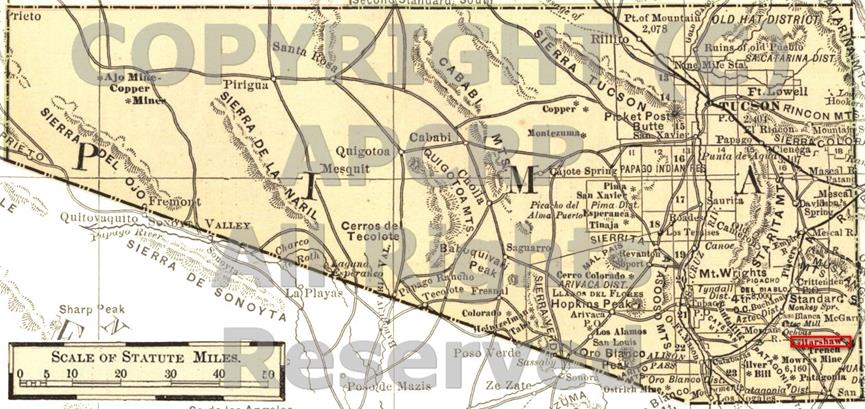

|

1883

map showing Harshaw, Pima County, became part of Santa Cruz County in 1899. Courtesy

Wikipedia. |

The Harshaw Post Office was established

on April 29, 1880 and operated until March 4, 1903. It got mail service on the

Southern Pacific Railroad via Tombstone three times a week, then brought to

Harshaw on stagecoach.

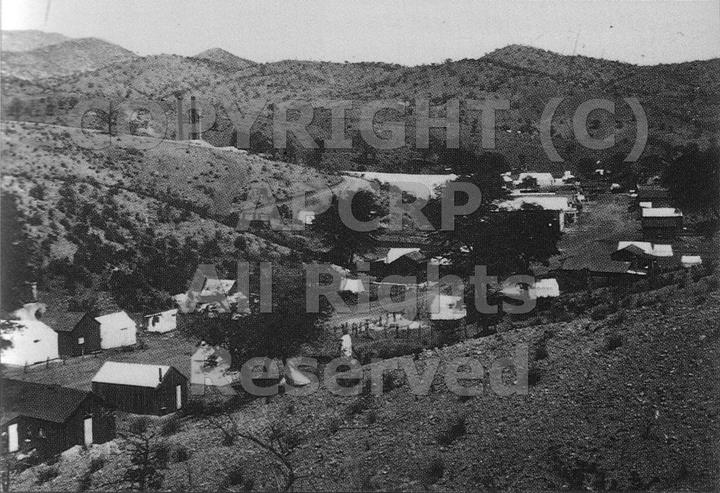

|

Harshaw mill 1879. |

Like most mining communities work in the

mines of the area had peaks and valleys. In 1887 Harshaw saw a rebirth by a

Tucson man named James Finley who purchased the Hermosa claim for $600. The

rebirth was minor compared to Harshaw’s peak production. The revival supported

approximately 100 people for a six year span but once again, new mining activity

was doomed by the death of Finley and the market price of silver dropped once

again.

|

|

Within a two mile radius of Harshaw

there were some twenty five mines, making Harshaw a very active business

community, plus having a stamp mill to process ore produced at the surrounding

mines if they didn’t have their own mills.

In 1937 another revival of the area

happened, via the Arizona Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) reopening

nearby Flux and Trench Mines, continuing operations until 1956.

|

|

Harshaw in 1880 boasted a one-mile long

main street: seven saloons, a boarding house, hotel, miscellaneous retail

businesses, including 8 to 10 general stores, and a newspaper called the Arizona Bullion occupied structures

along Main Street. There were 30 commercial buildings in all out of about 200

buildings.

The 1880 Census listed a population of

847 in Harshaw, compared to 9,743 in Tucson, and a total of 17,504 for Pima

County.

In 1881 the town suffered a fire,

caused by accident, and also fires in 1882 caused by severe thunderstorms.

There was at the same time a dramatic drop in quality of the ore, subsequently,

some of the population moved on to more prosperous opportunities. The first

fire is described in an article, over a month later, in the Arizona Weekly

Citizen, Nov. 30, 1881:

Harshaw

Fire, October 23, 1881:

Tonight, at almost 9 o'clock, the cry of

fire was heard. It broke out in the St. Charles Hotel, and it is supposed to

have been on account of the explosion of a lamp in the hallway of the hotel. At

the time it was thought the whole upper town was a goner, and through the

exertions of the many men they stopped its headway. The mill blew its whistle and was closed and

all the men from the mill and mine came to the scene and helped. The loses are

as follows: St. Charles Hotel, owned by Henri de Beauford, estimate to $2,000

covered by insurance; damage to John Husher's livery stable, about $150, no

insurance; cabin of S.H. Drachman, $125, no insurance. There was plenty of

water hands, which was a great help. A. Goldberg

& Sons a short time ago had 30,000 pounds of barley in Drachman's house

that was destroyed, but had fortunately removed it a few days before the fire. Mr.

A. Goldberg returns thanks for the efforts of the people of Harshaw in trying

to save Mr. S. Drachman's property."

One statistic that suggests Harshaw

didn't die after 1882 fires is the fact, reported in the April 28,1882 Arizona

Citizen by the schoolteacher, Mrs. N. G. Dunn, that there were 21 children

enrolled in school, with 45 days absence out of 365, and average attendance

176.7 days. Many students were listed

with perfect attendance!

The

Arizona Citizen (Tucson), Feb. 12, 1882 reported:

"The town of Harshaw is not dead

yet, although one of its citizens is now enjoying that defunct state. His name

is said to have been Pepper. He was engaged as water carrier to some of the

works above town and is said to leave a wife and six children in Oakland,

California. At the time of his death he, with some others, had escorted a

drunken woman to her room and left her, but returning shortly afterwards

attempted to force an entrance, when he was, by the woman, shot through the

bowels. He died near noon on the day following. That same evening two of the

legal fraternity punched each other with a free good will and later on one of

the Judges 'kicked my dog and then I kicked him.' One man killed, two judges

with discolored optics and another judge with a sore head, and all within six hours.

Nothing mean about Harshaw even if it is a little quiet."

Nogales

International News, July 10, 2015 reported:

A story details the efforts first by

Miguel Soto, who died several years ago, to record the history of those buried

in the well-maintained main Harshaw cemetery.

His family members, including Henry Soto, then age 67, and younger

brother Juan Soto, then age 61, are restoring short bios that were framed and

placed on gravesites about a decade ago. Juan explained, "These are

honoring those ancestors. We are who we are because of them." The text on the grave of Miguel T. Soto

(1883-Aug.9, 1957) said: "He was born in Florence, Arizona in 1883 and

died in Harshaw in 1957. He was a miner and cowboy, plus had many other

abilities."

The house the Soto family lived in still

stands near the main Harshaw Cemetery, and is used for a family retreat. The

remaining buildings in town are derelict.

|

Red grave indicates Angel Soto and

Soto family in upper right corner. Copyright Aaron Walton, used with

permission. |

Recent research has found eighty-six

documented burials in the main Harshaw Cemetery. Seven documented and unmarked

burials in Harshaw Cemetery South, which is across Harshaw Road and a few

hundred yards south of the main cemetery.

These and the flu deaths are listed in three separate rosters

accompanying this article. The first documented burial in the main Harshaw

Cemetery was John C. Marston. He was born in Jonesport, Washington, Maine, on

Oct. 21, 1818 and died Nov. 9, 1880.

The Harshaw Cemetery South's first

documented burial was also in 1880. A marker for Royal Hulburd gives his

birthdate as Jan. 26, 1831, in Stockholm, and his death date as Dec. 9, 1880.

Read details of their lives in the

rosters, and in tragedies of the family in this obituary for James Higgins in The

Border Vidette, Nogales, Arizona, November 28, 1914:

"James Higgins, a miner employed as

a hoist man at the World's Fair Mine, died at Harshaw last Sunday morning of

miner's consumption. Saturday Higgins was in Patagonia and complained of not

feeling well, saying he had been in poor health for some time, but his sudden

death came as a surprise to his friends. He was buried in the cemetery at

Harshaw. He left a wife and several children. Higgins was known to nearly

everyone in this part of the state as 'Strongboy,' a sobriquet he had earned by

physical prowess. Although of frail build he was remarkably strong until the

disease which caused his death fastened itself upon him. Higgins came to this country in 1882 from

Idaho and Montana, and was about 50 years of age at the time of his death. He had always been identified with mining,

and was liked by all who knew him for his many fine traits of character."

The Death Certificate for James Higgins

states he was born in July, 1872, in Ireland, and died Nov. 15, 1914, of heart

disease and consumption. He had a son, James Jr., who was born Nov. 14,

1914 - the day before James' death - and only lived 12 months and 16 days

before dying on Nov. 30, 1915, of "inflammation of bowels." The birth

certificate for the son states his father, James Higgins, was 42 years old, a

miner, and his mother was Catholina Martinez, Mexican, 31 years old, born in

Arizona. James Jr. is also buried in Harshaw Cemetery. James Sr. and his wife also

had a daughter, Margaret, born July 14, 1913, as "one of three

living children." There was possibly another son, Antonio, born,

date unknown, who died at the estimated age of 13 on Dec. 18, 1928, from a

compound fracture of the back of his skull from a fall into an open well. The

family then lived in Patagonia, a mile from the Nogales City limits. Antonio is

buried in Nogales Cemetery along with his mother, spelled "Catalina"

on her death certificate. She is described as the widow of James, and died Feb.

17, 1938, age 53, of carcinoma of the cancer and uterus.

|

Alhira B. Sorrells (1839-1907) rear, Bertie May Sorrells (1900-1902) right, Freddie Lee Sorrells (1880-1885) left. Photo courtesy Aaron Walton. |

|

|

Maria Medina (1947-1948) on left and

Pablo Medina (1920-2001) on right. Maria plaque reads: "Cristo es la luz

De Nuesto sen Dero. (Christ is the light of our path) Photo courtesy Aaron Walton. |

Grave

of Pablo Lopez Acevedo (1919-1949). Photo

courtesy Aaron Walton |

|

|

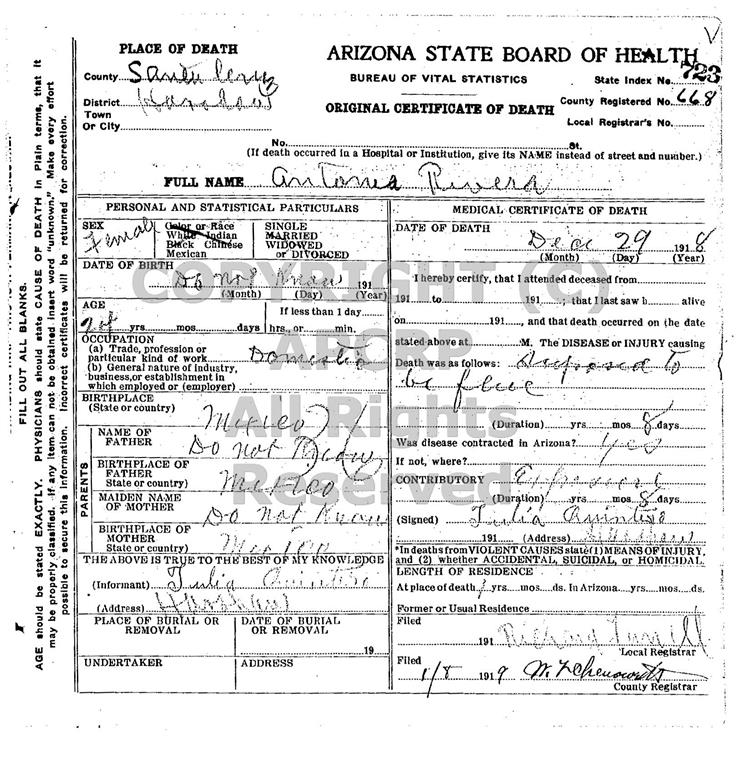

Harshaw had at least 14 deaths from the

influenza epidemic of 1918-1919. Some

curious DCs were found. The victims were all given a cause of death as

"supposed flue (sic)" with some secondary causes as

"exposure." None were seen by a doctor, various informants wrote the

identical phrases. All were signed by Richard Farrell, a prominent Justice of

the Peace and Registrar in Harshaw. (His son was Nick Farrell, shot to death,

described next.) Only a few had actual birth dates, most listed as

"unknown" with an estimated age. Many were born in Mexico. But, the

mystery lies in the fact that all of the deaths from flu listed NO BURIAL

PLACE. These burials are listed on a separate roster for Harshaw. Were they

buried in a mass grave or cremated? Are some of the unknown graves within the cemeteries

actually flu victims? Because of the fear and stigmas created by the epidemic,

its possible deaths were somewhat covered up so that family members would not

be quarantined? Or lose work? Or were their residences burned with the remains

inside (cremation) as was the custom, in an attempt to restrict further spread

of the flu.

One tragic death of a member of a prominent

family was noted in The Arizona Republican and other local papers

in December, 1921. Nick Farrell (1885 to November 30, 1921) was shot to death

during an argument with his friend John Chapman in a cabin near Nogales,

Arizona, within half a mile from the Mexican border. Chapman, a rancher, had

stopped a fist fight between Farrell and a cowboy named Bee Lewis, at 7:30 p.m.

Farrell then shot at Chapman, who fired five shots in return with a 32.20

six-shooter. The shots hit Farrell on the upper part of the chin, and emerged

from the chin into his breast and into his arms. "The shot did not badly

mutilate the body." Chapman surrendered to the Cochise County sheriff

after he phoned for a doctor. Eventually, a coroner's jury concluded he'd fired

in self-defense.

Ironically, almost three years earlier,

on November 27, 1918, Nick Farrell was cleared by a coroner's jury of murder!

He had been passing the house in Harshaw of Reyes Morales and found Morales

arguing with Felipe Gradillas. Fearing they would engage in a fight, he was

attempting to pacify them when Morales lunged at him with a dagger. Farrell

then shot Morales to death with a pistol, and Gradillas threatened Farrell with

his pistol, so Farrell shot Gradillas also, who died the next day. Both men

were taken to Nogales and buried in Nogales after the coroner's jury viewed the

bodies.

Excerpts from an obituary for Nick

Farrell in the Arizona Republican, December 02, 1921, tell more about

his family, and his burial in Harshaw Cemetery:

"World's champion broncho buster

is killed at Nogales. Nick Farrell, a

well-known cattleman of this county who was shot and killed recently was buried

yesterday afternoon in the Harshaw Cemetery....Farrell's body was taken to the

home of the parents, former state Senator and Mrs. Richard Farrell in Harshaw.

The funeral yesterday was attended by a large number of friends of the dead

man....Farrell, who at one time was champion broncho buster and steer roper of

the United States, was born and raised in Harshaw. He is survived by his widow

and six children (3 sons and 3 daughters)....Both Farrell and Chapman are

members of families well-known in this part of Arizona. Farrell's father,

Richard Farrell, formerly was a state senator from this county and now is

justice of the peace at Harshaw. Mrs. Farrell, who is teaching school at

Washington Camp, near Harshaw, is a member of a wealthy St. Louis

family...."

Note:

Richard Farrell (1847 - Jan.17, 1931) died of chronic myocarditis and

nephritis, and is buried in Patagonia Cemetery. Wife Ellen Farrell (1858-March

30, 1931) died of apoplexy and is also buried in Patagonia Cemetery.

Nick Farrell's grave is in Harshaw

Cemetery South and is marked by a square cement stone etched with a mountain

peak that has trees below it and a large tree to the right above his name

NICOLAS FARRELL, then 1886 in lower left and 1922 in lower right corners.

The cemeteries are on land managed by

the Forest Service and no new burials are permitted. The access is via a

gravel road, called Harshaw Road.

According to the July 10, 2015 article

about the Soto family, the old Harshaw Cemetery is one of several dozen

historic graveyards in the county. Burials reflect mining, ranching, and

colonial history of the area. Santa Cruz County is apparently making an effort

to map out the locations of all cemeteries in the county. APCRP continues

research on some of these cemeteries, including nearby Mowry.

|

Remains of Harshaw adobe structure,

2014. |

If you visit these final resting places,

reflect on frontier lives in these then remote mining areas! The town site became part of the Coronado

National Forest in 1953. Not much remains of Harshaw: a few houses, some

building foundations, the two cemeteries, and old mine shafts. Most of the

buildings were torn down by locals for building materials or by the Forest

Service in the mid to late 1970's.

|

James Finley house in 2014. Photo Courtesy

Wikipedia. |

There are several historic buildings

still standing, including the James Finley house built in 1877 (he was a mine

manager), foundations of the Hermosa Mill, assay office, small church, a two

room schoolhouse, remains of adobe houses, pool hall, and several other partial

wood and adobe structures. Some structures are on posted private property.

There are signs cautioning against

camping overnight in the area, due to concerns over illegal immigrant/drug

traffic through well-used smuggling corridors.

Harshaw is fairly close to the Mexican border.

There are many internet sites detailing

travel and points of interest in this area. A main route to Harshaw also could

take you to Patagonia and Mowry, also former silver mining towns.

Driving

Directions

From Tucson: Take I-19 south to AZ 83S.

Exit 281 toward Sonoita, Patagonia. After 25 miles, turn right onto W. Highway AZ

82. Travel about 14 miles to Harshaw Road, which is less than a mile past Beaty

Lane. The main cemetery is easily visible on a hillside by the road.

The

author wishes to extend a "Thank you" to:

Neal Du Shane, APCRP, for the Google map

of the cemeteries, and posting this article and the cemetery rosters on

APCRP.org.

Bonnie Helten, APCRP Certified

Coordinator, for proofreading this article.

Aaron Walton, who gave permission to

use four of his fine copyrighted photos of Harshaw Cemetery.

Wikipedia: domain maps and photos.

In memory of my late husband, Ed Block,

who originally visited and photographed Harshaw Cemetery with me, back in 1999,

and helped me write the original article on Harshaw for APCRP.

Sources:

Wikipedia: information, public domain photos and maps.

Old newspapers on the Library of Congress web site:

Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

Find-A-Grave: Harshaw Cemetery and Harshaw South Cemetery.

Additional information on burials from Family Search web site:

FamilySearch.org.

Death Certificate records on the Arizona state web site:

Genealogy.Az.gov.

Miscellaneous articles regarding Harshaw on the internet.

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet

Presentation

Version 042020

Second

Edition

Webmaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright © 2020 Neal Du

Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be

used

for personal family history purposes, but not for commercial or financial

profit.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer &

Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

Well-kept graves in

Well-kept graves in