HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 030812-BC

HUMBUG, Arizona - 2012

Story and photos by

Bruce Colbert

|

Humbug, AZ Photo Neal Du Shane |

Editor’s note: This

was the 7th Annual Humbug Potluck and Open House hosted by Dave

Burns and Theresa Thayer, Humbug’s caretakers and preservationists. Humbug is

located along Humbug Creek in the foothills of the southern portion of the

Bradshaw Mountains north of Lake Pleasant. Dave opens the gate to Humbug for

visitors each year on the first full (two-day) weekend in March.

On the road to Humbug,

the dust kicked up by a caravan of Jeeps, 4x4s and nimble ATVs could blind a

camel. But you don’t care when you pass by ancient saguaros close enough to

reach out and touch; turn a corner and gasp at the breathtaking view of miles

of unspoiled mountains and magnificent desert; and white-knuckle your way over

old mule trails with sheer rock walls on one side, and seemingly bottomless

drop-offs on the other. This is the West dreams are made of, movies filmed

about, and legends born from.

|

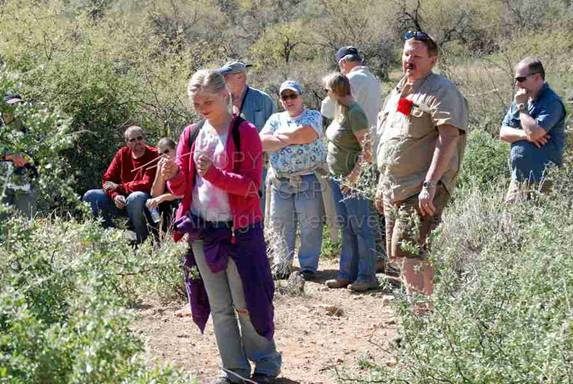

Sarah

Munsell tries identifying unmarked graves for the

first time |

When little Sarah Munsell showed up at Humbug ghost town’s potluck and open

house Saturday morning, March 3, she wracked up some

unique “firsts” in her young life.

“I’ve never been to a ghost town like

this,” said the petite 8-year-old. She also did not believe a person could

identify graves the same way you search for water.

“I didn’t believe him,” she said

referring to Neal Du Shane, founder of the Arizona Pioneer Cemetery and Research

Project and grave researcher extraordinaire. “I thought he was moving (the

rods) with his hands. It was cool. The whole place is cool.”

Kathy Kent agreed with Sarah. She

heard about the open house “from my boyfriend” and joined him on the back of a

quad for a cross-country ride to check it out.

“I love the remoteness of the place,”

Kent said. She also tried her hand at identifying unmarked graves and joined

Sarah as a believer. “And the caretaker seems to meld right in like he’s part

of the scenery. I couldn’t imagine anyone but him taking care of this place.”

That caretaker is Dave Burns. Burns’

history is interwoven with Humbug’s history. “I was backpacking down the creek in

1981 when I first met Newt White,” Burns said. “I didn’t know anything about

Humbug; didn’t even know it was here.”

|

Dave Burns points out historic landmarks at Humbug |

When he met Newt along Humbug Creek,

Burns was a 15-year-old adventurous teen. He and the grizzled old miner struck

up a friendship. Newt was already a living legend among miners, ranchers and

cowboys in Yavapai and Maricopa counties.

“Newt knew every rock and bush out in

the desert,” Burns said with a chuckle remembering his departed friend and

desert mentor. “He’d tell me where to find something with directions like, ‘Go

this far, turn at that rock, and look behind a certain bush.’ And it would be

right there. It was amazing.”

In 1922, at the ripe old age of about

14, Edward Newton “Newt” White and his father arrived at the northern end of

the Sonora Desert. They stayed at Rock Springs (adjacent to Black Canyon City)

for a spell, and then found their way out to the Champie Guest Ranch. Newt took

a job as a go-fer at the popular dude ranch, but his father got restless and

moved on.

At Champie Ranch, Newt learned to

cowboy. While out herding cattle by himself one day, Newt’s horse spooked and

took off at a run throwing Newt in the process. His left leg caught in a

stirrup and the horse dragged him full gallop through thick patches of cholla and prickly pear cacti. By the time other

ranch-hands found him and got him to a Phoenix hospital, it was too late and

doctors had to amputate his left leg. Someone carved him a few wooden

prosthetics. Over time, Newt apparently left wood legs scattered at various

places in and around the Bradshaw Mountains: Cathy Cordes, manager of Cordes

General Store near Mayer, has one; and Burns said he has another one.

“When I met Newt, he was the caretaker

here,” Burns said. The energetic teen started helping Newt at Humbug, and after

Newt died in 1997, Burns became the town’s full-time caretaker. “Newt had

worked for Frank Hyde at Humbug.” Hyde died in 1973.

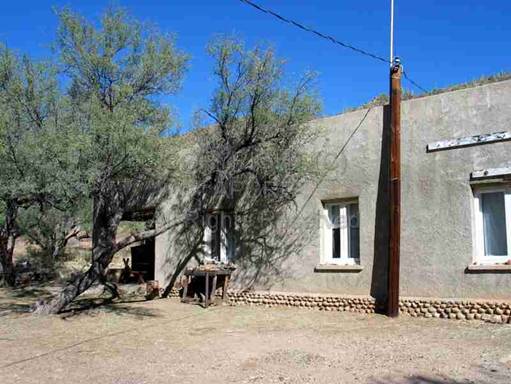

Frank de Lacey Hyde, a New York

stockbroker, came out West on a trip and fell heads-over-heels in love with

Humbug. He bought every mining claim in the district he could get his hands on,

and in 1932 he built his wife, Elizabeth, and their infant daughter, Carolyn, a

large adobe “mansion” that commanded a view of Humbug and its namesake creek.

Hyde’s “Big House” stands today, although it is showing its age, and the desert

has reclaimed the lush and intricate terraced gardens planted and tended by

Elizabeth.

“I love the old adobe, and I loved

seeing the old Kelvinator refrigerator sitting there,” Kathy Kent said of the

former Hyde home. “It’s such a juxtaposition to the

rest of the house.”

|

Humbug’s Miner's Quarters and Residence.

Photo Neal Du Shane |

Frank Hyde’s (Main) House. Photo

Neal Du Shane |

After Du Shane finished his

finding-unmarked-graves lesson and cemetery history talk, visitors explored the

ruins, walked where miners walked and snapped photographs galore. Two touring groups

formed up: one rode out to visit the site of the former town of Columbia and

its four-stamp mill; and the other group rode up the side of a low mountain to

see the Pero Bonito Mine.

|

Bruce Colbert (Author) & Kathy Kent

at El Perro Bonito Mine above Humbug |

One of the interesting things about

visiting historical places is that their names can sometimes be as intriguing

as the place itself.

Take Pero

Bonito, for example. Some historical journals refer to the mine as the El Pero Bonito, others the Pero

Bonita, and some uncouth historian spelled it as one word: Perobonito.

In Spanish, pero bonito translates as “but nice,”

which doesn’t make a lot of sense for a name of a mine. However, if it was

actually called El Perro Bonito (two “r’s”,) that would make it “the

pretty dog.” It’s still an unusual name, but it makes more sense for the name

of a mine or if you owned a pretty dog that hung around the mine. The State of

Arizona Department of Mines lists it as Pero Bonito.

So, the mine’s original name may have been different from what we know it as

today.

|

Driveway out of Humbug Creek entering Humbug |

Then there is “Humbug.” In the

mid-1800s, rumors flew amongst miners about an unnamed creek teeming with gold

ready for the taking. After slogging up and down the creek without much luck,

the miners scoffed at the humbug rumors of gold in the creek. In old English

vernacular, “humbug” meant false talk or a deception - a sham. Miners being

miners, they called the seemingly barren creek the Damn Humbug Creek. The early

cartographers opted for something more politically correct, and simply

shortened it to Humbug Creek.

Although the creek may not have been the

rumored bonanza, gold flowed from the mines. Enough that Humbug had its own

stamp mill and red light district.

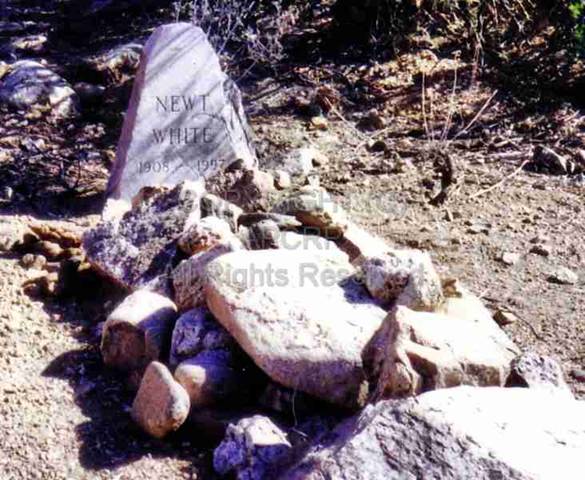

Neal Du Shane met Dave Burns while

researching the history and locations of the Humbug and Columbia towns and

their cemeteries.

“We got to talking and I asked Dave

about any cemeteries at Humbug,” Du Shane said. “He was reluctant to say at

first, but eventually he showed me where Newt is buried.” Still skeptical about

grave dowsing, Burns decided to test Du Shane.

“He said to show him where Newt is,”

Du Shane said. “I dowsed the grave but didn’t get any reaction from the rods.

But when I did the headstone the rods crossed.” Crossed rods indicate a male

grave and opened rods indicate a female, Du Shane explained.

|

Newt White’s grave at the Humbug Cemetery. Photo Neal Du Shane |

“Dave said, ‘You’re right. Newt was

cremated and the urn is buried under the headstone.’” Another believer was

born. Eventually, Burns told Du Shane about a potluck he held at Humbug the

previous year, and from that talk came the current

annual Humbug open house and potluck.

There’s something magical here that

sets people’s imaginations loose.

“I like holding the open house because

it gives people a chance to see Humbug’s history,” Du Shane said. “It is

authentic history. Dave likes to say he keeps Humbug maintained, not preserved.

It is totally undisturbed.”

Kathy Kent could not agree more. She

summed up the weekend about the way most people probably felt after leaving.

“I loved riding out there through the

saguaro forests. They’re so majestic, so old and spectacular,” she enthused.

“It’s like going through a time warp. The further back we went, the further

back in time we went. I just found it fascinating.

“It was so stimulating to see their

culture, to see how the miners lived in the middle of nowhere. Where did they

get their water, their food? How long did it take to get from Phoenix to Humbug

on foot or horseback? I just feel very privileged to be a part of it. That to

me is a wonder in itself.”

As a town, Humbug is dead for sure.

But it still is full of life for visitors. The saguaros, sagebrush and

cottonwoods are still here. The miners, soiled doves and moonshiners are gone,

but the streets and trails still carry people to the mines, dead-end test holes

and abandoned home sites.

Adobe walls still stand weathering

year after year the same thunderstorms, wind and heat that wracked the little

town back in its hey-day. The sound of picks and shovels and the rolling

thunder of dynamite blasts are gone, but the birds still chirp, and when it

flows, that damn Humbug creek still gurgles, and gentle breezes still follow

its course through the little valley.

For more information about Humbug,

Arizona and other ghost towns and cemeteries, visit www.apcrp.org

|

Once glowed brightly at Humbug |

Adobe await a new meaning to life |

|

Resting after years of hard production |

Ready for a new day |

|

Truck, tack building in center and stables on right |

Dust to Dust – Adobe melt in progress |

American

Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 030812-BC

Webmaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright

© 2012 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website

may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for

financial profit or gain.

All contents of this website are willed to the

AmericanPioneer & Cemetery Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS