HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

N34* 16’ 29.32”, W112* 16’ 40.22” (WGS84)

Elevation 3,966

Middelton vs. Middleton:

The creek for which the community resided is spelled

Middleton Creek. It was named for mine promoter George. W. Middleton. While

most historical information spells it Middelton. In the photograph below, the

We are a welcome

sight at the Middelton depot as we deliver fresh vegetables and bolts of cloth

ordered from

Compare and Contrast: Middelton on March 28, 2008.

The railroad right of way is still visible, compared to the 1906 photograph.

Photo courtesy: Neal Du Shane

Table of Contents

Arrival of Railroad in Crazy

Basin

Bradshaw Mountain Railroad Map

Middleton

Post Office Re-established

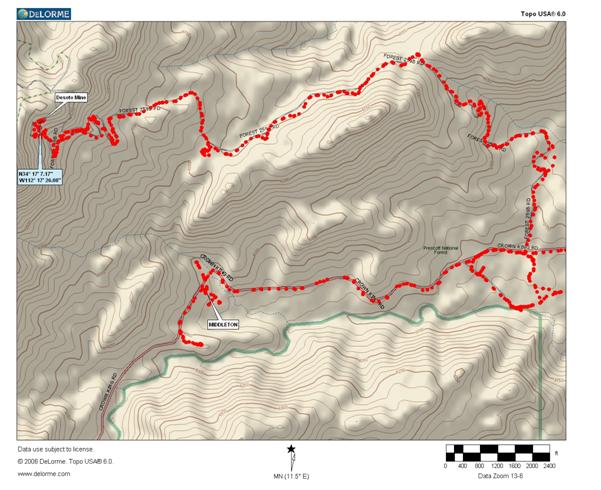

Map to

De Soto Mine from Middelton

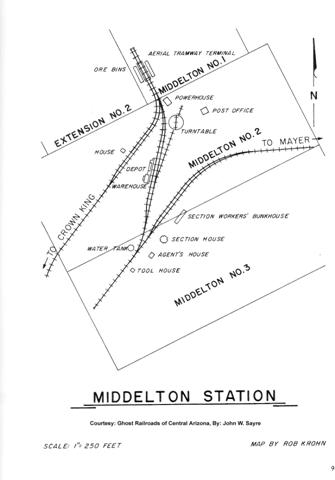

MIDDELTON STATION

1903 – 1932

Courtesy: Ghost Railways of

By: John W. Sayre

The route of the Bradshaw Mountain Railway, like the

Although the area was prospected as many as ten years

earlier, the De Soto Mine was not discovered until September 1875. The mine was

originally called the Buster Copper Mine but was also known at various times

throughout the years as the Copper Cobre, Bradshaw Mountain Mine, and the name

by which it is generally known-the De Soto: The early tunnels and operation of

the mine centered on the north side of the ridge, although exploration on the

southern slope was extensive. A short distance west of the

A small mining camp west of the

Arrival of Railroad in Crazy Basin

The arrival of the railroad in

Bradshaw Mountain

Tramway

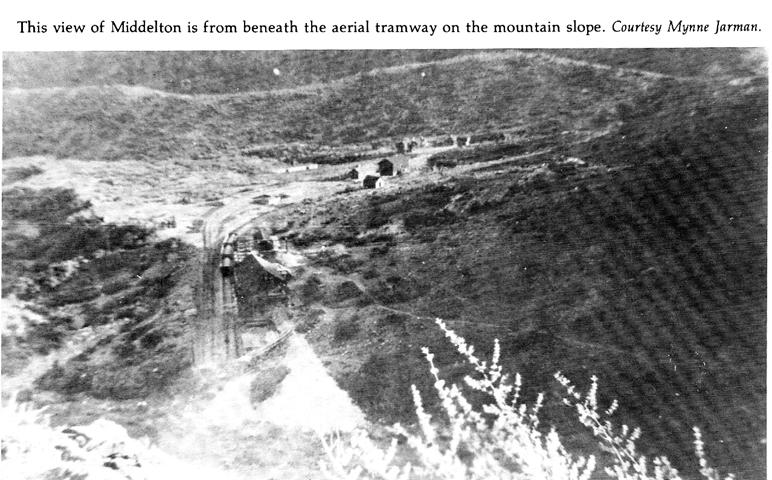

The elevation of the mountain on

which the De Soto Mine resides is 5,533’ at the top. The elevation of the De

Soto Mine was 5,366’ and the elevation of Middelton is 3,966’. An elevation

gain of 1,400’ or 27% grade. A road some 7.5 miles leads from Middelton (

The

tramway, which was the best money could buy, was completed in April 1904. It

was designed by the Blechert Transportanlagen Company of

The

tramway, which was the best money could buy, was completed in April 1904. It

was designed by the Blechert Transportanlagen Company of

While the tramway was being built on the mountain slope, Middelton was also the site of considerable construction activity. The railroad decided to make Middelton, which was halfway between Mayer and Crown King, the base camp for its maintenance workers. The site served as a temporary home for the construction crews as" they worked their way toward Crown King and was later made the permanent camp of the men responsible for maintaining railroad track and property on the Bradshaw Mountain Line. The railroad built a section workers' bunkhouse which was similar to a dormitory and also constructed a separate dwelling for the foreman and his family.

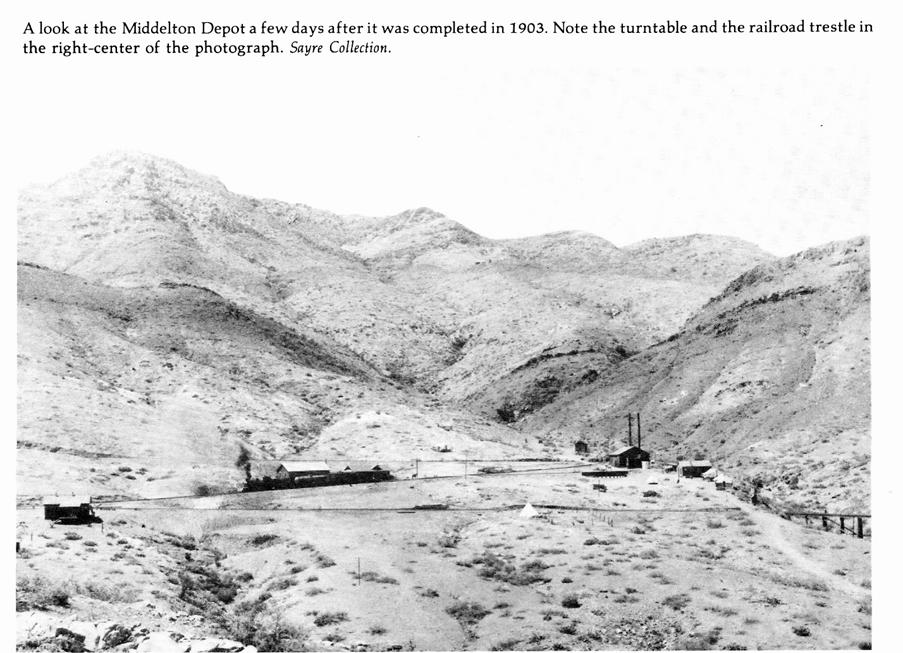

The railroad built and maintained numerous other

buildings and structures in Middelton. The depot, which measured twelve by

forty-eight feet, was connected by a wooden platform to a large adjacent

warehouse. A house was built for the station agent assigned to the depot, and

two other dwellings were built in the community for various purposes. A water

tank, tool shed, and assorted platforms and storage structures were also

railroad property in Middelton. During the days of track construction between

the town and Crown King, a turntable was placed in Middelton to allow the

engines to change directions for the trip back to

In addition to the railroad, several other enterprises

were represented in Middelton. The mining company owned the tramway terminal

and a large powerhouse and maintained an office in the community. Wells Fargo

and

Frank Murphy took an early interest in the De Soto

Mine. A first-rate businessman and promoter in his own right, Murphy had

contacts and friends in all the right places. He was advised and kept abreast

of mineral discoveries and noteworthy mining developments. Murphy invested in

several mines, and considering the risk of that type of investment, he did

rather well. He knew George Middelton, the developer of the De Soto Mine. The

mine and Murphy's railroad presumably were discussed whenever the two met.

Several factors indicate that Murphy was involved .with the mine ownership

either directly or indirectly as early as 1902. By 1905, he served on the Board

of Directors of the Arizona Smelting Company, which owned the mine.

Unfortunately, the

Entrepreneurs attempted to duplicate the successful efforts of Charles Wingfield in Huron and Leverett Nellis in Turkey Creek by establishing saloons in Middelton. The town and De Soto Mine supported two saloons: one owned by Thomas Hogan, the other operated by Robert J. Schwanbeck. Schwanbeck was the first to open his doors in Middelton, doing so in 1903 shortly after the rail reached the community. Schwanbeck and his competitor never achieved the success they sought. Hogan stayed only briefly, while Schwanbeck eventually moved his establishment to Humboldt.

Schwanbeck and his wife attained a degree of

notoriety for an event which occurred in 1907. Accidents were relatively common

to mining and railroad towns. Often the experience of a miner or a railroader

was measured by the number of scars he wore or by the number of fingers he was

missing. The Schwanbeck mishap of September 1907 was a bit unusual even in a

community accustomed to injuries. While pushing a baby stroller along the road

in front of her house in Middelton, Mrs. Schwanbeck was bitten on the ankle by

a large diamondback rattlesnake. Her husband was notified immediately and

arrived home within fifteen minutes. He quickly opened the wound with his razor

and in heroic fashion sucked the poison from it with his mouth. When the doctor

from Crown King reached Middelton to attend to the woman, he found her

experiencing some pain but past the crisis stage. However, Mr. Schwanbeck was

extremely ill as he had swallowed some of the poison while sucking it from the

wound. After treatment, he recovered and was a good deal wiser for his

experience. A lengthy article appeared in the

Middelton Station Map

First

Shipment - 1904

In 1904 when ore was first shipped over the Bradshaw Mountain Line from Middelton, the total production of the entire Peck Mining District was only $83. With the luxury of the railroad, this annual figure increased rapidly and reached $307,213 by 1906. Production and ore shipments received a major setback, however, in September 1904 when the Val Verde smelter burned to the ground. Without a local smelter to process its ore and due to poor financial decisions, the company that operated the De Soto Mine was forced into bankruptcy.

De

Soto

N34* 17’ 7.17”, W112* 17’ 26.08” (WGS84)

Elevation 5,366

The

De Soto Mine lay dormant, and the miners left town. The merchants, in search of

trade, were forced to leave Middelton. The post office was discontinued on 31

January 1908. The railroad depot was closed and boarded up; the agent's house

was empty and neglected. Wells Fargo and

The

De Soto Mine lay dormant, and the miners left town. The merchants, in search of

trade, were forced to leave Middelton. The post office was discontinued on 31

January 1908. The railroad depot was closed and boarded up; the agent's house

was empty and neglected. Wells Fargo and

With the railroad, large-scale operation of the mine

disproved the proclamations that the

Reactivated – 1914

The town deteriorated until the mine was reactivated in 1914. During the mine's inactivity, the railroad leased two of its dwellings in Middelton to a rancher who raised cattle nearby. His dozen cattle outnumbered the human population of the community through the end of 1914. The loss of the powerhouse and one of the old saloon buildings to fire reduced the number of buildings in town, but the livestock and reptile population didn't seem to mind.

World War I

The

enormous demand for copper generated by World War I reopened the De Soto Mine.

The mine's ownership had undergone several reorganizations and was solvent by

1914. In August of that year, crews reconditioned the aerial tramway.

Technological advances and improved mining methods made the mine very

profitable, but the aspirations of ten years earlier were dashed forever.

Miners returned to town, rail traffic increased, and more railroad employees

were assigned to the community.

The

enormous demand for copper generated by World War I reopened the De Soto Mine.

The mine's ownership had undergone several reorganizations and was solvent by

1914. In August of that year, crews reconditioned the aerial tramway.

Technological advances and improved mining methods made the mine very

profitable, but the aspirations of ten years earlier were dashed forever.

Miners returned to town, rail traffic increased, and more railroad employees

were assigned to the community.

The town of

Middleton Post Office Re-established

After a year of effort, the community was successful in having a post office re-established on 13 January 1916. In accordance with United States Postal Service regulations, which prohibited the recognition of a previously discontinued post office branch, another name had to be selected for the community's new post office. The name chosen was Ocotillo, and Pearl Orr was named the postmistress.

The residents of Middelton

were employees of either the mining company or the railroad and their families.

Middelton, during the years of World War I, housed approximately one hundred

people. The miners were primarily Europeans, and the railroad section workers

were mainly Mexicans. Supplies and fresh produce were generally ordered by

telephone from

Recreation

Recreation in Middelton was simple yet satisfying. Dances were the favorite pastime of the men and were held often in Crown King and Turkey Creek. The bunkhouses witnessed innumerable card games, as that was also a popular form of entertainment. On the few occasions when snow stayed on the ground, snowball fights and throwing snowballs at the railroad water tank were cold but fun activities. Once a year, a traveling band of gypsies visited the community. The group's "dancing" bear was always a big hit with men and women and boys and girls of all ages. In late August, an annual picnic was held near Crown King. It included homemade ice cream, wild grapes, and walnuts. These annual events were delightful highlights for the residents of Middelton.

A dependable water supply was important to the railroad and the community. Most of the town's water came from the Blanco White Spring over a mile away. The railroad piped the water from the spring to its water tank in Middelton. Another small local well was also used to meet the town's water needs. Yet another well and spring on the mountainside were not very reliable, and water for the boardinghouse at the mine was shipped up from Middelton via the tramway.

Despite the hardships, the townspeople were happy and stayed relatively healthy considering their isolation and occupations. If they did "take ill" country doctors in Mayer and Crown King still made house calls. Hospitals in Humboldt, Prescott, and McCabe (until 1907) treated the severely injured. Those that medical science could not help were buried in little cemeteries that still dot the countryside.

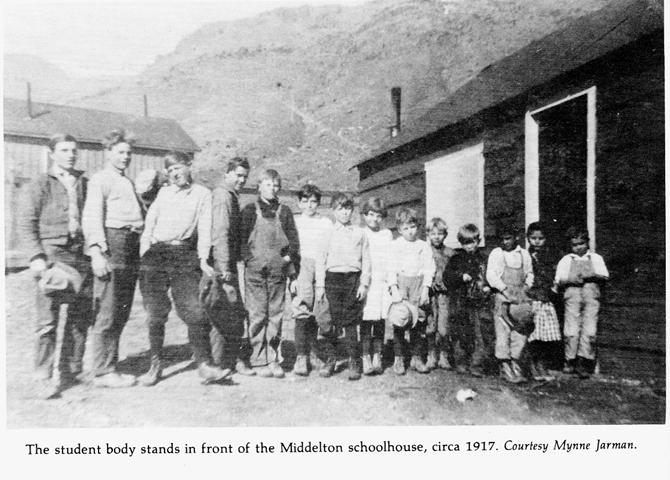

Middleton School

L-R Bob Orr, Ernie Orr, ?, ?, Floyd Orr, ?, ?, Ruth Orr, ?, ?, Jack Orr Sr., ?, ?, ?,

Names provided by Jack Orr Jr. 05/06/08 thanks to Todd Zuercher.

The majority of Middelton residents were single men; however, enough children were present by 1917 to necessitate the construction of a schoolhouse. The enrollment of the small, red, wooden structure never exceeded fourteen pupils, yet it housed all eight grades. Almost as important to the townsfolk was the wooden flagpole which stood beside the school. The American flag waved proudly from the pole for many years. Middelton's population never warranted such refinements as a church, fire department, or police force. The county sheriff was called whenever lawlessness required his presence.

Voting a Serious Matter

Although all the refinements of urban living were not present in Middelton, the residents of the community displayed civic pride. Voting was a privilege which was taken very seriously. Votes were cast in Middelton between 1904 and 1908; however, after the town was revived in 1915, the voters traveled to Turkey Creek to cast their ballots. Middelton was always well-represented at the polls.

Middleton Utilities

Although strong in spirit, Middelton lacked many of the "modern" conveniences. The luxury of electricity was never enjoyed by the community. Some of the buildings on the hillside near the mine had electric lights, but most of them also relied upon kerosene lamps, as did the populace of Middelton. Telephone service was installed to the mine prior to 1901, but Middelton did not obtain this utility until 1915 when a party line running from Mayer to Crown King was installed. Roads led from Crown King and Turkey Creek to Middelton, but their poor condition prevented any but the sturdiest vehicles from reaching Middelton.

The railroad depot in

Middelton was vacant during World War I, but the town witnessed increased

railroad activity. The train crossed the trestle on the outskirts of town many

times over the years. The sidings in Middelton could hold twenty-eight cars and

were often filled to near capacity. Many of the ore cars were empty and

destined for Crown King while others awaited copper ore from the

Although the De Soto

Mine produced a great deal of ore during World War I, it failed to live up to

the expectations of its owners. In 1919, development work enlarged the limits

of the ore bodies already known but did not result in any new discoveries. The

days of great activity were numbered, as the company considered the mine to be

completely developed and resigned itself to work it out gradually in accordance

with market conditions. Work was discontinued at the property in 1922, and the

mine was considered exhausted. The total yield of the De Soto Mine at that time

was $3,250,000, which made it one of the largest producers in the

Hectic Days Past

The days of hectic activity

in Middelton had passed. Fewer than a dozen railroad employees made up the

town's population as activity at the De Soto Mine ceased. On 15 June 1925, the

Ocotillo Post Office in Middelton was discontinued. Middelton had a ghostly

look in 1926 when a small company leased the

Railway Fell into Disuse

The Crown King Branch of the Bradshaw Mountain Railway fell into disuse and was abandoned. The tracks were pulled up and removed in sections beginning in 1926 with the Crown King to Middelton segment. The rail remained in Middelton until 1932, when it retreated even farther. The railroad razed the structures it owned along its right-of-way, which included its buildings in Middelton. The deserted schoolhouse and two abandoned residences were all that remained. These structures were burned, wrecked, or carried off by vandals, thieves, and natural elements prior to 1946. A similar fate befell the buildings at the mine site with the exception of a portion of the upper tramway terminal and several tramway towers, which still remain.

Middelton Deserted

Today, Middelton and the surrounding area are deserted. The De Soto Mine, lying high on the rugged mountain slope from which more than $3,250,000 worth ore was carved, is silent. A stiff wind screams in its loneliness as it blows down the mountainside and across the abandoned landscape that was once filled with promise. The weathered and fallen timbers of the Bleichert aerial tramway, miles of frayed cables, and the weed overgrown railroad switchbacks are the last vestiges of the thriving Middelton community.

A small portion of the remains of the lofty De Soto Mine

Photo Courtesy: Neal Du Shane 03/28/08

Looking Southeast at 5,366’ Elevation

Head tailing pile of the De Soto Mine

Photograph by: Neal Du Shane 3/28/08

Map to De Soto

Middelton Cemetery

Our research detected no sign of a cemetery at Middelton proper. A short 1.5 mile distance down stream and old arrestra was found and graves numbering approximately 20 in number where identified there. The most noticeable was a miner who died in 1898 and his grave has a concrete enclosure below.

It is very likely this was a community cemetery serving the area. Also deaths after the rail road would have very likely been loaded on the train and shipped to Prescott or Crown King if – if the person or family could afford the expense. Otherwise the person would very likely have been interred here.

Photo by: Neal Du Shane 3/28/08

APCRP - Internet Edition

Version 050608

Published – Photograph Enhancement by: Neal Du Shane

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright ©2003-2008 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of any kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS