HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 063309

Revised 041312

THE SKELETON CAVE MASSACRE

By Kathy Block

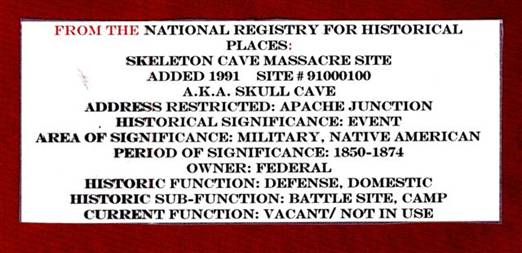

The sparse entry for the Skeleton Cave Massacre Site doesn't even hint at the tragic events that took place there. Here's an attempt to fill in the details of this little-known story.

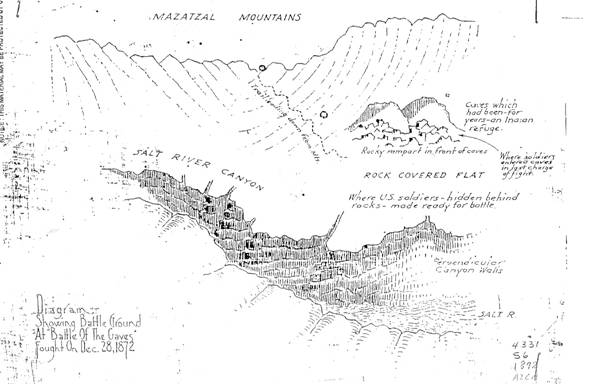

I. SCENE OF THE TRAGEDY: SKELETON CAVE.

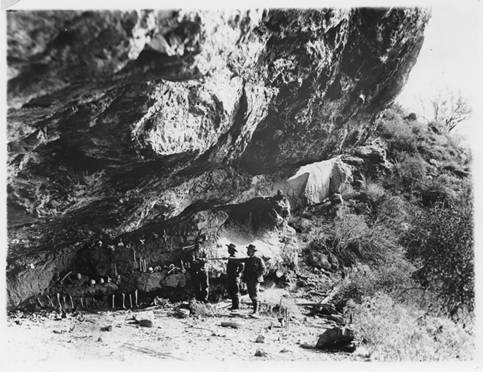

Skeleton Cave is actually a rock shelter, formed by an overhang at the base of a cliff, in lava. It is situated about 1,200 feet above the backwaters of Apache Lake, formed by Horse Mesa Dam, on the north wall of a canyon west of Horse Mesa Dam. It is reached by a steep perilous climb either up from below or down from above, to an elevation of about 2,450 feet. Skeleton Cave, which was also known as Apache Cave and Skull Cave, will not be precisely located in this article. The Forest Service, which manages the area, has indicated that they are under no obligation to give out coordinates for the cave because it holds sacred significance to the local Native Americans.

The cave is roughly semi-circular with the open side of the circle facing southwest. Looking into the cave, the left side is deeper than the right. The height of the ceiling descends steeply from a maximum height of 25 feet at the entrance to less than a foot along the back wall. The maximum depth from front to back is about 40 feet. Width from corner to corner is 118 feet. On the right side is a sloping platform about 30 feet long, 12 feet wide, and 8 feet higher than the floor in the center. Above the platform is a small area 12 feet by 12 feet which would have been the most protected position within the cave. The floor is covered with dirt and rock deposits. Outside the cave are several large boulders that have broken from the cliff above, with brush between them and the entrance. This area was the best sheltered defensive position for the Yavapais. Beyond the boulders is a steep boulder-strewn drop off down the drainage. There are several natural paths leading to the cave along the cliff face.

Unfortunately, the cave has been looted, as noted in an application for the National Register of Historic Places. Some relics and artifacts shown in early photos of the cave taken when it was rediscovered by a cowboy, Jefferson Davis Adams, in 1906, were gone in later explorations; and in the period 1905 to 1911 more looting occurred during construction of Roosevelt Dam. In 1984 a Phoenix outdoor writer pictured material in his column taken from the site. The dirt floor toward the back of the shelter has been dug down at least 3 feet by illegal digging and screening. Apparently metal detectors have been used also. The bones of the massacre victims were removed around 1933, sixty-one years later, and reburied at Fort McDowell by the Yavapai. (More information to follow).

Figure 1 - Entrance to Skeleton Cave

Looking into Skeleton Cave, bones from massacre visible.

Figure 2 - Map of Skeleton Cave

II. MAIN PARTICIPANTS IN THE SKELETON CAVE MASSACRE

Accounts of the events mention some key people. Here's a description of who they were.

GENERAL GEORGE CROOK

George Crook was 9th of 10 children born September 8, 1828 to Thomas and Elizabeth Crook of Taylorville, Ohio. His father was a farmer who had emigrated from Maryland to Ohio after the war of 1812. He had been described as having a taciturn, self-confident, phlegmatic character. He was prepared to be a farmer and was seen as academically undistinguished. He graduated from West Point, U.S. Military Academy, in 1852, ranking near the bottom of his class, graduating 38th out of 43! He was considered by the Academy as slow to pick up on concepts, but he never had to relearn them once mastered. Upon graduation, Crook was known as self-assured, unflappable and emotionally remote. One of the few friends he made was Philip H. Sheridan and their careers crossed many times in the next 40 years.

Here are a few highlights of Crook's long military career, 1852 to 1890. Crook began his career with the 4th US Infantry as Brevet 2nd Lieutenant, serving in California 1852-1861. He fought against several Native American tribes in Oregon and Northern California and was severely wounded by an Indian arrow in 1857 in the Pitt River Expedition.

After the Civil War, Crook fought in more Indian wars. In 1872 just before the Skeleton Cave Massacre, Crook was appointed Brigadier General in the regular Army, a promotion that passed over and angered several full colonels next in line for promotion to general.

After the massacre, he served against the Sioux during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. By 1882 Crook was back in command in Arizona.

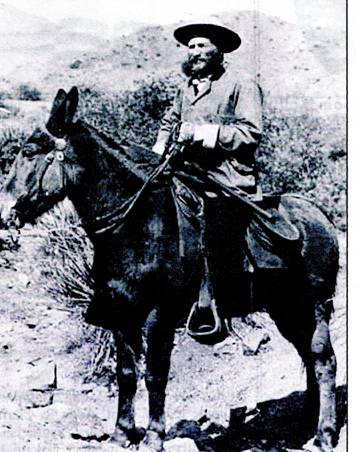

In his later years, George Crook apparently had an unorthodox appearance. He had great cotton-candy mounds of gray muttonchops sideburns that covered most of the lower half of his face, above which protruded a strong, straight nose and piercing deep-set blue eyes. His main trademark was that he almost never wore a uniform, but preferred overalls or a canvas suit. He liked to wear a conical hat, such as that worn by a Japanese farmer at work in a rice field. He carried a shotgun instead of standard Springfield Army rifle. He preferred to ride a mule, named Apache, an animal he insisted was far superior to a horse.

Crook spent his last years speaking out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries.

Crook died of heart failure in Chicago on March 21, 1890, still on active duty in the Army.

Figure 3 - General Crook on his mule.

CAPTAIN WILLIAM H. BROWN

Captain William H. Brown led 130 troopers from the 5th U.S. Cavalry Regiment and 30 Apache scouts to attack the Yavapai men, women, and children in Skeleton Cave. He also participated in later military operations against the Apache.

CAPTAIN JOHN GREGORY BOURKE

Captain John Gregory Bourke was "first of all a soldier." He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 23, 1843 to Irish immigrant parents, Edward Joseph and Anna Morton Bourke. He grew up in a comfortable "book filled" home and early education included Latin, Greek, and Gaelic. The Civil War began when he was 14 years old; at 16 he ran away and lied about his age. He said he was 19 years old and enlisted in the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry as a Private. He served three years of Civil War action and received the Medal of Honor for "gallantry in action" in Stone River, Tennessee.

Afterwards, Bourke graduated in June, 1869 from West Point and placed eleventh in a class of thirty-nine. (In comparison to General Crook.) He received his Second Lieutenants commission in his lifetime regiment, the 3rd United States Cavalry.

After a brief interval at Fort Craig, New Mexico Territory, he became General George Crook's aide-de-camp and served Crook as adjunct and engineering officer in the actions against the Apaches for 16 years from 1870 to 1886. He was known for his scholarship, powers of observation, and writing ability. He was given time off from his field duties to live among and study the Indians of Arizona. Because he was a skilled language scholar, he learned the Apache language. He kept lengthy, detailed diaries of his experiences, which he used for prolific writing during the last ten years of his life (1886-1896) that added to knowledge of Native Americans and their customs. His best known memoir is, "On the Border with Crook," 1891. (Often referenced by historians.) Another famous writer, Sigmund Freud, wrote the preface for Bourke's "Scatologic Rites of All Nations." Altogether, ten books were written by Bourke.

Just two weeks before his fiftieth birthday, on June 8, 1896, Bourke died from an aneurysm of the aorta in Philadelphia.

HOO-MOO-THY-AH ("Wet Nose"), later known as Mike Burns.

The story of Hoo-Moo-Thy-Ah has become known by the recent publication of his autobiography, The Journey of a Yavapai Indian: A 19th Century Odyssey, He had unsuccessfully spent many years in the latter part of his life struggling to publish his manuscript, which was stored in fragments in state archives until 2002. He played a major role in the Skeleton Cave Massacre.

Hoo-Moo-Thy-Ah (hereafter referred to as Mike Burns), was born into Yavapai family in Arizona, just before the establishment of Ft. McDowell, built by the U.S. Government to subjugate Native American peoples. His birthplace, around 1864, was near the Four Peaks Mountains, near Tonto Basin. In his autobiography he remembered the time as of "great beauty and happiness." However, when he was about 5 years old, his life was altered forever. His mother was killed by soldiers out on a patrol. She apparently ran for her life and crawled in a rock hole. She was pulled out and shot several times. After her murder, his father became a bitter enemy of the "Hayko" (enemy) and would often go with friends to the Salt River Valley just to kill any "Hayko" they could. The young boy was left responsible for the care of his younger brother and sister.

Then, when Hoo-Moo-Thy-Ah was about eight years old, he was sent by his father to accompany his uncle to Wipuk (in the Sedona country) to bring back a horse. They were surprised by a patrol and the uncle deserted him. The terrified boy hid himself in a hole in a rock while the soldiers camped nearby. It became night and he almost froze to death, in a snowstorm, wearing only a G-string. They had been camped near Four Peaks, about 7,645 elevation in the Mazatzals. When he emerged the next morning, he was captured by the soldiers, whom he considered true demons. The captors remembered his valiant but vain struggle and after he lost, he was dragged over the rocks "like a log." The capture was in the winter of 1872 and General Crook was beginning his Tonto campaign.

The terrified child was taken to Captain James Burns, Six days later he was forced to lead the soldiers and Maricopa and Pima scouts to Skeleton Cave and witnessed the massacre of over 60 of his people, including his father and siblings, grandfather, uncle and aunt. He was shown the body of his grandfather, who had part of his head in a little rock hole.

The boy was taken back to Fort McDowell and given to Lt .E.D. Thomas, who named him "Mike Burns", with the explanation that "Mickey" would be at least one Irish Indian in Arizona! He was then given back to Captain Burns, but when Burns died, in 1874, Mike was given to Captain Hall S. Bishop. For the next 30 years, Hoo-Moo-Thy-Ah acted as scout and interpreter for the army against Native Amerian tribes of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. But he was also educated, at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a controversial off-reservation school in Carlisle, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, operated 1879-1918, and Highland University in New Mexico, where he was an outstanding student and trained as a teacher. He also worked for a while on a farm in New York.

He returned to Arizona in the early 1900s and became a rancher and woodcutter near Fort. McDowell, where he raised a family who still live in the area. He died November 16, 1934 at Fort McDowell, and is buried in the cemetery there.

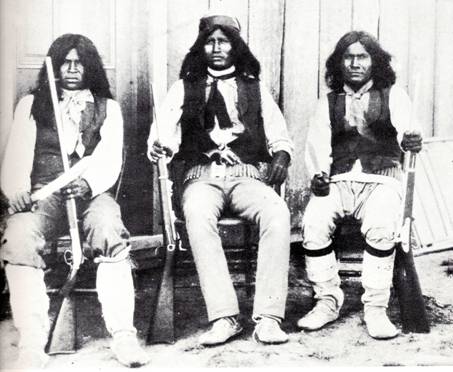

THE APACHE SCOUTS

Most accounts of General Crook's campaigns in the Indian Wars consider the use of "Apache Scouts" to be his most effect tool and singularly responsible for his success and the end of the Indian Wars in Arizona. Because the nature of the warfare near Skeleton Cave was of a hit and run style, the Apache scouts were ideal, being used to attacking, when the least risk to them was present, then leave with their spoils - usually livestock and weapons. If they were pursued, they'd split up and link up later. They knew the terrain, could move quickly, silently, and farther than their pursuers, and could live off the land. The frontier Army was unable and ill-suited to use these tactics of fighting.

Realizing the advantages of using these scouts, General Crook began to actively recruit the unit that became known as his "Apache Scouts". In actuality, there were scouts from many other tribes as well, such as Pima and Maricopa. The scouts were best used according to their own concept of scouting and tracking, not the Army's. Crook deliberately chose younger, junior officers who would be more flexible in their outlooks and more successful in leading this new type of soldier.

The best known Apache Scout recruited was named Alchesay, who was from the White Mountain Apache Tribe. He would join Crook on many of his campaigns and served as a valued advisor. (The White Mountain Apaches still hold him in high esteem today.) Another group of scouts were Arivaipa Indians. They worked with Captain Brown.

The Apache Scouts worked with the army by moving ahead of the soldiers looking for signs of the enemy. Additional groups moved along the flanks of the column. Often the advance guard would initiate and finish the fight before the main body could get up to their location. Most of Crook's columns would consist of the scouts, mobile infantry-cavalry units, and mule pack trains. He'd direct these columns to remain in the field until they were successful. His philosophy was to track the insurgents, and destroy them with the overwhelming firepower of the columns. The men could stay longer in the field due to the improved logistics provided by the mule pack train. The system developed by General Crook eventually wore the insurgent Apache bands down until they were forced to accept defeat. The conduct of these Scouts in the Skeleton Cave Massacre will be discussed later.

The value placed on these Apache Scouts is seen by the fact that in April, 1875 after the Skeleton Cave Massacre, ten of the scouts were recommended by Crook to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for "gallant conduct during campaigns and engagements with Apaches during the winter campaign of 1872/73." Bourke gushed, "The names of many scouts, guides and packers of that onerous, dangerous and crushing campaign (1872-1873) should be inscribed on the brightest page in the annals of Arizona, and locked up in her archives that future generations might do them honor."

The Scouts who received these honors had names such as: Alchesay, Jim, Elsatsoosn, Machoi, Blanquet, Chiquito, Kelsay, Kasoha, Nantaje, Nannasaddi. In March 1875, the Medal of Honor was conferred and Arizona had the first 10 medals unofficially accredited to the state. Why "unofficially?" Because for seven of the scouts, either the enlistment information was lost or not completed, and the place of enlistment for these men was not included in their citations. According to the rules of the medal, without a verifiable place of enlistment, the medal is not "officially" attributed to that state. During the Indian War Period (1866-1890), nearly 40 percent of all Medals of Honor were for actions that took place in Arizona Territory!

Figure 4 - Apache Scouts.

Photo by C.S. Fly, 1870's.

THE APACHES AND YAVAPAI, CRUCIAL DIFFERENCES BETWEN THEM

One of the great tragedies of the Skeleton Cave Massacres is that the Yavapai were mistaken for Apaches, though there were crucial differences between the two. Early settlers and military recognized some differences between the groups. The southeastern or Ft. McDowell group was simply called "Apache" as they seemed indistinguishable from the several Western Apache bands. In the decades of Indian warfare in Arizona, the name "Yavapai" faded into disuse and any raids by the Yavapai were blamed on "the Apaches". At the time of the Massacre, books and magazines referred to the victims as Apaches. Nineteenth century writers usually referred to the groups of Yavapais separately until the name "Yavapai" came into general use. Mike Burns, the captured boy, made it plain in his autobiography that his people were Yavapai. (Confusing!!!)

To Whites in those days, they all looked alike, and an Indian was an Indian, better dead than alive. The confusion in calling Yavapai by the name Apache does not sit well with today's Yavapai, who feel it cheats them out of a unique heritage. Many newspaper and magazine accounts in the late 1800s stated "the better dead than alive" phrases.

In rare books owned by the author Smithsonian Institute, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 30, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Ed. by Frederick Webb Hodge, (1907 and 1910) misstatements about these two tribes are perpetuated. The Yavapai are described as their name coming from "enyalva" (sun) and "pai" (people), i.e. "People of the Sun," and as a "Yuman tribe, popularly known as Apache Mohave and Mohave Apache, i.e. "hostile or warlike Mohave". The Apache, probably from "Apachu" (enemy), the Zuni name for the Navaho, were designated "Apaches de Nabaju" by the early Spaniards in New Mexico. The name has been applied also to some unrelated Yuman tribes as the Apache Mohave (Yavapai) and Apache Yuma. The Apaches call themselves "N'de, Dine, Tinde, or Inde"(People).

Ethnological writings describe some major differences between Yavapai and Apache peoples. Even sympathetic military personnel, who had opportunities to observe differences, recorded in their diaries that they were two separate peoples. Yavapai were described as taller, of more muscular build, well-proportioned and thickly featured while the Tonto Apaches were slight and less muscular, smaller of stature and finely featured. The Yavapai women were seen as stouter and having "handsomer" faces than the Yuma in the Smithsonian report. Another difference, which could probably not have been noticed at long range, was that the Yavapai were often tattooed, while Apaches seldom had tattoos. Painted designs on faces were different, as were funeral practices. In clothing, Yavapai moccasins were rounded, whereas the Apaches had pointed toes. Both groups were hunter-gatherers, but were so similar here that scholars are seldom able to distinguish between their campsites.

Linguistically, at first two distinct languages were spoken. Bourke, General Crook's aide, recognized during campaigns of 1871-1874 (remember he learned Apache and was a skilled linguist), that they were dealing with separate tribes, but even then they mixed considerably. He said most of them spoke both languages, and the headman of each band usually had two names, one from each tradition. The language difference was the most definite indication that these are two distinct people. By 1965, when a study was made by David M. Brugge, tracing names used in the two languages as they were spoken in central Arizona Indian communities, he was able to tell the amount of mixing that had taken place. He suggested that the Yavapai were already there when the Apaches moved in and mixing began. The Apaches dominated Yavapai culture as they moved into the Rim Country westward. Over the generations the Yavapai adopted Apache clan systems and their material cultures became identical. One exception was the Tonto Apaches, who have a dialect different from the other Western Apaches. This slight "Yavapai" accent led other Western Apaches to call them "Foolish" or "Tonto" because their dialect sounded foolish to them! (Origin of name "Tonto" for that area of Arizona?)

The people killed in the Skeleton Cave Massacre were Yavapais, though identified by early accounts as Apache. That's because, according to one account, they sometimes joined in raids with Western Apaches and thus were often thought to be Apache themselves. A common term for them in the Nineteenth Century was "Apache-Mohaves". As noted, they spoke a language entirely different from any Apachean dialect. They weren't even part of the same large family as Apaches, being a Yuman people rather than Athapaskan. Unfortunately, these differences were "beyond the understanding of Crook and his soldiers."

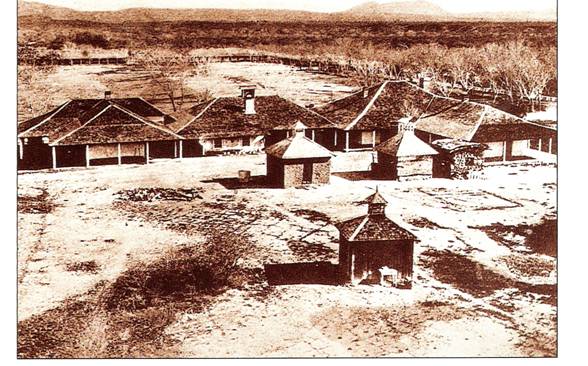

FORT McDOWELL

Fort McDowell was established on the west bank of the Verde River in 1865. It was also called Camp Verde or Camp Green and was deep in Apache and Yavapai country. The Fort was renamed after Major General Irwin McDowell, made famous for his loss of the first large-scale battle of the Civil War! It was considered one of the finest and most solid posts in Arizona Territory, despite the fact that it proved so hot in the summers that soldiers carried their beds outside to sleep under the stars. The McDowell Mountains are two miles to the east. Because of its location nearly a day's ride from Arizona's main overland route, the Army had excessive freight costs and unreliable transportation. An experiment was attempted in 1866 to build a half-section farm with a four-mile irrigation canal. An unintended consequence was that the produce supplied most of the post's needs and civilian farmers were hesitant to settle nearby, fearing they couldn't compete. In 1876 the Quartermaster concluded the farm was a mistake but crops were already in production in the Salt River Valley. Furthermore, Jack Swilling (see Jack Swilling) had organized a canal company to provide irrigation for Phoenix's ever-expanding farmland.

Fort McDowell did play a useful role in General Crook's 1872-1873 winter campaigns. Its purpose was to control the local tribes: the Yavapai and Apache Indians. It did not earn the status of a "fort" until 1878. With the Indians pacified, Fort McDowell closed in 1890.

After abandonment, its 25,688 acres were allocated by the Department of Interior for an Indian School, and to the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Tribe, now known as the Yavapai Tribe. Most of the old post is gone, except for melted adobe foundations. The tribe has recently constructed a library, museum, and archive to preserve the history of the Yavapai people. In June 1892 the military graves at the post cemetery were disinterred, and the remains shipped to the Presidio in San Francisco for reburial.

|

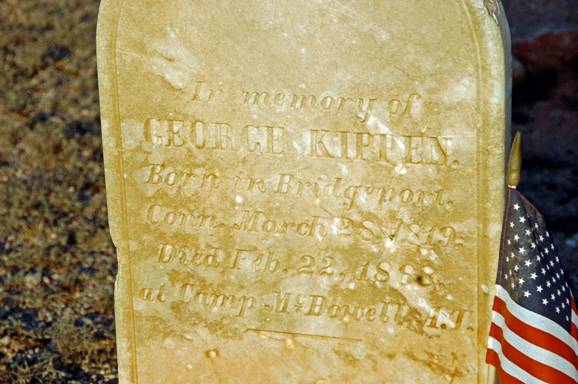

Photo by Neal Du Shane April 4, 2012 |

In memory of

GEORGE KIPPEN,

Born in Bridgeport,

Conn. March 28, 1819,

Died Feb. 22, 1868,

at Camp McDowell A.T. |

One civilian grave remained, that of George Kippen whose simple marble marker can be seen today among the Indian burials.

Dr. Carlos Montezuma, cousin of Mike Burns, became a medical doctor and outspoken leader for Indian rights, and was buried there in 1923, as is Mike Burns, in 1934. Some of Crook's Apache Scouts are buried there, including Alchesay. The remains of many from the Skeleton Cave Massacre have been interred there with a monument to mark the tragedy. Fort McDowell is located on Indian Route off AZ 87, north of Phoenix.

Figure 5 - Fort McDowell in the 1870s.

III. PRELUDES TO THE SKELETON CAVE MASSACRE

A long tangled history of clashes between Native Americans and Whites in the area led directly and indirectly to the Skeleton Cave Massacre. Diverse accounts and viewpoints make it difficult to sort out the "facts" in the chain of events during the conflicts.

A list of Cavalry actions versus Indians in 1832 thru 1898 includes the fact that after the Civil War the United States concentrated on reconstruction of the Southern cities. But the Army had to continue to engage in battle with Indian tribes, who remained hostile and wanted to keep their lands free of encroaching settlers. Supposedly, the Indians "swept down in hordes, showing little compassion, ravaging settlements or ranches, torturing captives, scalping and mutilating the dead, stripping corpses and using them for target practice." The Cavalry was brought in because the Infantry was unfamiliar with the territory. The primary focus of their battles were the Apaches. One example was the murder of 14 miners who attempted to cross Apache Pass in 1861. Cavalry approached from the opposite direction and although they were ambushed, were able to hold out with artillery fire until reinforcements arrived. The "shooting wagons", as the Indians described them, were able to kill 60 warriors with only 4 Cavalry casualties. Apache Chief Mangus Coloradas was gravely wounded.

Indian incidents around Prescott became so bad that the January 22, 1870 Prescott Miner published a list of the dates and locations of 300 whites killed in the area!

News accounts of Cavalry actions fueled anti-Indian sentiments and retaliatory raids and attacks on sometimes peaceful Indian settlements by miners and settlers. An example such inflammatory news is this account from May 18, 1871, about a year and a half before the Skeleton Cave Massacre. Entitled WAGON TRAIN MASSACRE, it reported an incident near Salt Creek Prairie, Texas; the Apaches allowed a small wagon train to pass thru safely, then attacked the larger train that followed. A teamster who escaped described what happened to a wounded teamster as, "Tied his head down on wagon wheel, ripping out his tongue and built a fire under his face, then took axes, cutting him to pieces.

A famous early explorer and prospector named Pauline Weaver apparently got along with most Indians. He taught them to say "Pauline-Tobacco" to indicate they were friendly when approaching whites. But, when the area near present day Stanton and Rich Hill became overpopulated with newcomers, who were unaware of the custom, killings began. Even Weaver wasn't immune and was attacked by a war party and badly wounded. He'd performed a "death song" when attacked by Yavapais. They believed he was insane and left the scene immediately. Weaver was able to return home and recover. The Yavapais supposedly made inquiries for months afterwards about their friend "Paulino."

Another viewpoint of events leading to the tragedy is from the Wickenburg area. The discovery of gold by Henry Wickenburg and the establishment of the Vulture Mine drew miners and ranchers and farmers, who built homes along the Hassayampa River. As the number of settlers, both American and Mexican, grew near Wickenburg, founded in 1863, they encroached on the Yavapai Indians, who lived, farmed, and hunted along the Hassayampa River. These settlers staked out mining and water-rights claims, raised livestock (mainly cattle) that damaged vegetation and springs, and drove out native animals which the Yavapais used for meat. The settlers decided to eradicate the Yavapais and initiated a series of planned raids against them. The Yavapai fought back. Approximately 1,000 Yavapai Indians and 400 settlers died in the so called "Indian Wars" during 1860-1869. The U.S. Army convinced the Yavapai to resettle on a permanent reservation, but because the government supplied inadequate rations, the Yavapai began to raid stagecoaches and wagon trains and isolated settlers and miners. The historic Wickenburg Massacre, November 5, 1871 (a little more than a year before the Skeleton Cave Massacre,) was west of Wickenburg, not far from the Date Creek Reservation where nearly 1,000 Tonto Apache and Yavapai Indians had settled. This became a "flash point" for a war that had been brewing for years as incoming settlers clashed with people who had possessed the land for generations. (See www.apcrp.org) The discovery of gold along Lynx Creek by the Walker party in 1863 brought more miners. Fort Whipple and Prescott were built to the north.

Prior to this time, another widely publicized incident was the Oatman family massacre in 1851, in which a band of Indians identified as Yavapai ambushed the family as they traveled en route from Missouri to Yuma on the Gila River Trail. Royce Oatman and his wife and four of their children were killed, one son Lorenzo was left for dead but survived, while sisters Olive and Mary Ann were later sold to Mohaves as slaves. The sisters were forced to watch as their captors killed their parents. Five years later Lorenzo, after a frustrating campaign to find and rescue his sisters, was able to ransom Olive from the Mohave Indians. (Oatman Massacre)

A well-known proverb reflects increasing anti-Indian sentiment of the 1870s and earlier: "The only good Indian is a dead Indian." The history of the origins and growth of this proverb and its use by prominent politicians and generals shows that this saying became very widespread in the United States and even Canada. Very briefly, in one famous incident, Old Toch-a-way, a chief of the Comanches in January 1869 said, "Me, Tock-a-way; me good Injun.:" General Philip Sheridan set those standing by "in a roar" by saying,"The only good Indians I ever saw were dead." General Sheridan (1831-1888) repeatedly denied making such a statement, reported by eyewitness Captain Charles Nordstrom and reported in Edward Ellis in The History of Our Country: From the Discovery of America to the Present Time, 1895. But Sheridan was known as a bigot and Indian hater. He had been a lifetime friend of General Crook.

An even more blatant example of the attitudes of some of the politicians and government agents was stated not many years before the Massacre by Representative James Michael Cavanaugh from Montana on May 28, 1868 during debate, in the U.S. House of Representatives, on an "Indian Appropriation Bill." Excerpts tell the story: "I will say frankly that, in my judgment, the entire Indian policy of the country is wrong from its very inception. In the first place you offer a premium for rascality by paying a beggarly pittance to your Indian agents......I like an Indian better dead than living. I have never in my life seen a good Indian (and I have seen thousands) except when I have seen a dead Indian.....I believe in the policy that exterminates the Indians, drives them outside the boundaries of civilization, because you cannot civilize them. Gentlemen may call this very harsh language, but perhaps they would not think so if they had had my experience in Minnesota and Colorado. In Minnesota the almost living babe has been torn from its mother's womb; and I have seen the child, with its young heart palpitating, nailed to the window-sill....I have seen women and children brought in scalped. Scalped why? Simply because the Indian was 'upon the war path,' to satisfy the devilish and barbarous propensities. The Indian will make a treaty in the fall, and in the spring he is again 'upon the war path.' The torch, the scalping-knife, plunder, and desolation follow wherever the Indian goes,,,,"

Brief mention should be made, also, of Cochise, a strong six-foot tall chief of the Chiricahua Apaches. He had a special hatred for the white man. In 1861 he was unjustly accused of stealing a small boy from a ranch near Fort Buchanan. The boy, later known as Mickey Free, had actually been kidnapped by Pinal Apaches. A Lt. George Bascom, of the Seventh Cavalry camped near Apache Pass, tried to force Cochise to return the boy by trying to capture him when he came to Bascom's tent to talk. Cochise escaped, gathered his followers, and captured several white men as hostages. The exchange was never made, and three Indian hostages were hanged. Cochise began a war and said, "I was at peace with the whites, until they tried to kill me for what other Indians did; now I live and die at war with them." He is known to have burned 13 white men alive, tortured 5 to death by cutting small pieces from their feet, and dragged 15 to their death at the end of a lariat! Cochise made a temporary peace in September, 1871, with General Gordon Granger at the Indian agency at Canada Alamosa. He was promised a home, but refused a reservation offered at Tularosa.

Then, on April 30, 1871, the Camp Grant massacre occurred, a prelude to further massacres and violence. After Apaches at Canada Alamosa were removed to Tularosa valley in the Mogollon Mountains, despite objections from Cochise, the Chief (one of Crook's main enemies and targets) and his warriors went back to their home in southern Arizona. Other Apaches who sought peace left their rancherias in the wilds and came in to Camp Grant for protection. In February 1871 Eskiminzin, chief of the Arivaipa Apaches, with 150 followers came to Camp Grant. They were poor, they said, and hungry, tired of being hunted and killed. They wanted a place to live in peace. Lt. Royal E. Whitman, commander at Camp Grant, believed them and gave them a place near the post on land which had once belonged to the Apaches.

Settlers in nearby Tucson were alarmed and spoke of Indian raids in the vicinity, for which Eskiminzin was unjustly blamed. The infuriated civilians focused on this peaceful Apache village in retaliation for an Apache raid on American settlers. When the Army had refused to help, on April 28, 1871, a party of 6 Americans, 48 Mexicans, and 92 Papago Indians gathered in Pantano Wash, east of Tucson. Two days later the mob, armed by the Adjunct-General of Arizona Territory, attacked the unsuspecting camp of Arivaipas. Most of the warriors, including the chief, were off in the mountains, hunting. Women, old men and children were left to be killed. In a few minutes 128 helpless people (some accounts say 144 people, all but 8 of the dead being women and children) were massacred. Twenty-nine children were taken captive and sold as slaves by the Papagoes in Sonora, or kept as servants by the residents of Tucson. All the dead were buried by the Army around the camp. White participants in the massacre were later tried in Tucson and acquitted. To murder an Indian was no crime under the laws of Arizona Territory. Camp Grant was located on the west side of the San Pedro River where Aravaipa Creek meets the San Pedro River, between Mammouth and Winkleman. Today the site is used by Central Arizona College.

Not long after the Camp Grant massacre, General George Crook (a Lt. Colonel at the time) was sent to replace General Stoneman as commander of Arizona Territory on June 4, 1871.General Stoneman had been partly blamed for actions leading to the Camp Grant Massacre. President Grant ordered a two-pronged program to end the Apache wars. Crook tried peace, using a one-armed Civil War officer named General Oliver Howard, who would negotiate treaties with the tribes. Howard was able to negotiate a tentative peace with Cochise, partly through the aid of Tom Jeffords, superintendent of a mail line and a man who'd become friendly with Cochise. But, General Howard was unable to make peace treaties with the Yavapai and Tonto Apache in the central mountains, who defiantly rejected the peace proposals. President Grant then had no choice but to order General Crook into battle, and his winter campaign of 1872-73 began, leading to the tragic Skeleton Cave Massacre.

Clashes between settlers, the Cavalry, and Indians continued to escalate after the Camp Grant Massacre. Battles followed battles. The year of the Skeleton Cave Massacre, 1872, there were a series of clashes. May 23, the U.S. Cavalry engaged the Tonto Apaches at Sycamore Canyon, Arizona. July 13, during a fight between the U.S. Cavalry and hostile Indians at Whetstone Mountains (near Kartchner Caverns), Private Michael Glynn singlehandedly fought 8 Indians, killing or wounding 5, and driving the rest away. August 27, Sgt. James Brown, in command of a detachment of 3 troopers, defeated a larger force of hostile Indians at Davidson Canyon near Camp Crittendon, Arizona.

General Crook became convinced that only a decisive military defeat would force the Apache to settle permanently on reservations. Crook apparently looked for an excuse to launch his comprehensive war of attrition. He learned of a plot to kill him when he visited the Date Creek Reservation (where on September 8, during this visit, in a clash with the hostile Indians, a Sgt. Frank E. Hill, despite his severe wounds, captured a hostile Apache chief and received a Medal of Honor for his heroism.) A group of about 100 warriors and their families fled, fearing retaliation as Crook sought the conspirators. They fled to Skeleton Cave, seeking refuge in the shelter that had been used by generations of Yavapais, which became their tomb in the Skeleton Cave Massacre on Christmas Day, December 28, 1872.

Date Creek Reservation was near Camp Date Creek. (See APCRP). This camp, originally known as Camp McPherson, had been established in 1867 by the Army to guard the road between Prescott and LaPaz. It had moved several times. The name came from the abundance of yucca or wild dates in the area. An Army report in 1868 criticized the soldiers because they spent more time fixing buildings and prospecting than fighting Indians. In early 1871 it was established as a reservation for about 225 Apache-Mohave Indians, and was known as a "feeding station". Due to difficulties in supplying the Reservation with food, these Indians were transferred in June 1871 to Camp Verde. Camp Date Creek closed in 1874. It was located 60 miles S.W. of Prescott, north of U.S. 89 in Date Creek.

In conclusion, a series of raids, attacks, battles between various settlers, miners, military, and Indians (both Apache and Yavapai), and an increasingly anti-Indian sentiment reflected in news accounts, magazines, and speeches, set the events in motion that led to the Skeleton Cave Massacre.

IV. THE BATTLE AT SKELETON CAVE

An apt quote about history is: "History, though we seldom so think of it, is not really the story of what happened; history is necessarily the story of what is preserved in the record." The Battle at Skeleton Cave was recorded by Captain Burns, John Bourke, and General Crook in diaries and in official Cavalry reports. These reports stressed the role of the scouts and soldiers and their military tactics. A more intimate, human view was offered in the posthumous autobiography of Hoo-moo-thy-ah. An article on one web site stressed the use of the Sharp's rifle. Later historians in magazine articles and books attempted to condense and coordinate information from many sources. Readers of accounts, often far removed from the scene in the East coast, had varied and often negative reactions to what they perceived happened in far-off Arizona in a remote cave. Here's a generally agreed-upon outline of events of the Battle at Skeleton Cave.

General George Crook made a decision, based partly on false information that another Apache chief he sought, Delchay, a hostile anti-reservation chief, was hiding in the cave with a band of warriors. The military had been aware of reports that there was a hidden rancheria somewhere in the Salt River Canyon. When the frightened child, Hoo-moo-thy-ah, uncertain of his fate among the soldiers, was first captured, he pointed out to Captain Burns the location of the cave, by taking him to a ridge and telling him what he wanted to know.

The evening before the attack, Companies L and M, Fifth Calvary, commanded by Captain William H. Brown, accompanied by 30 Apache scouts, struggled through the snow-covered Superstition Mountains to join Company G of the same regiment, from Fort McDowell, with their 100 Pima Indians. This combined group was in the heart of hostile Apache country and "looking for a fight:" They were camped at the mouth of Cottonwood Creek on the Salt River. The native scouts, commanded by a half-breed named Archie MacIntosh, went ahead to look for this rancheria supposed to be in the Mazatzal or Four Peaks area, where Delche was possibly hiding. An Apache scout, named Nantaje (known to the soldiers as Joe), working with Major Brown, could lead the white men to the hiding place of the peoples. The plan was to surround and surprise the people in Skeleton Cave and bring an end to the attacks and powers of the chiefs and warriors. That night, the Apache scouts skinned a mule and feasted in anticipation of the fight.

At dawn, on a snowy Christmas Morning, December 28, 1872, the 130 man force led by Captain William H. Brown and Nantaje, used techniques learned from the scouts, and crept towards the cave with their moccasins stuffed with dry grass (instead of heavy Cavalry boots). Their footsteps were thus muffled as they worked their way on hard rocks towards the cave. Soldiers carried only bacon, bread, and a little coffee, and their guns and ammunition. Mules and surplus equipment were left behind.

Nantaje and MacIntosh led a detachment of six of the best shots under Lt. William J. Ross along a rough trail down the canyon of the Salado. A fall would have meant instant death. As they rounded a turn, there was the shelter on a shelf above the canyon, protected by great, smooth boulders that had fallen from the cliff. The soldiers fired on a small party, supposedly just back from a raid, who were hunched around a small fire in front of the cave. They hit many of their targets, who were silhouetted by the fire, killing at least six. Then, yells of surprise and hatred answered the soldiers from warriors inside the cave, who shot arrows in the general direction of the attack, but Ross and his men were safe behind rocks and he quickly rushed some of the men to rocks on the other side of the entrance.

Major Brown called on the supposed Apaches, who were actually Yavapai, to surrender. In defiance, one warrior supposedly climbed to the top of a rock some distance down the canyon and gave a yell of defiance and bared his buttocks. A blacksmith named John Cahill had his Sharp's rifle in position "like a flash" and shot the Indian. Another version is that the warrior had begun his war-whoop and 20 carbines were gleaming in the sunlight, 40 eyes were sighting along the barrels....Immediately the resounding volley had released another soul from its earthly casket, and let the bleeding corpse fall to the ground as limp as a wet moccasin." Bourke records that when the Yavapais were told to surrender, "The only answer was a shriek of hatred and defiance, threats of what we had to expect, yells of exultation at the thought that not one of us should ever see the light of another day.,,,They seemed to be abundantly provided with arrows and lances, and of the former they made no savings, but would send them flying high in the air in the hope that upon coming back to earth they might hit those of our rearguard."

According to an article about Sharp's carbines, Brown positioned his force so that "one-half was in reserve behind the skirmish line...with carbines loaded and cocked and a handful of cartridges on the clean rocks in front...the men on the first line had orders to fire as rapidly as they chose, directing aim against the roof of the cave, with the view to having the bullets glance down among the men, who had massed immediately back of the rock rampart." This plan worked "admirably", and the shots were "irritating the Yavapais to the degree that they no longer sought shelter, but boldly faced our fire and returned it with energy, the weapons of the men being reloaded by the women." These weapons were possibly Henry and Spencer rifles like those used in the Wickenburg Massacre.

The ricochets caught the victims huddled inside. Cries of wounded, and wails of frightened children showed the indirect fire was effective. Suddenly a death chant began. The Apache scouts warned, "Look out, there goes their death chant, they're going to charge." Charges followed from inside. The defenders were driven back with bloody losses, but the death chant continued. It was described as a "strange, haunting sound, half wail and half exultation, the frenzy of despair and the wild cry for revenge" by Captain Bourke.

At one point in the battle, a 4-year old boy ran to the mouth of the cave "and stood thumb in mouth, looking in speechless wonder and indignation at the belching barrels," wrote Bourke. "Almost immediately a bullet glanced off his skull, knocking him to the ground. Nantaje rushed forward and dragged the boy to safety amidst the cheers of the soldiers who stopped firing momentarily, then resumed with redoubled intensity."

The end of the Yavapai's brave resistance came when Troop G of the 5th Cavalry appeared on the overlook above the cave and rained rocks and bullets upon the Indians hiding out in the drainage below. A vivid account narrates how "screams of the dying pierced the dust, rising high in the air. Only echoes responded. The death chant was quiet. No rifle spoke. The cave was the house of the dead."

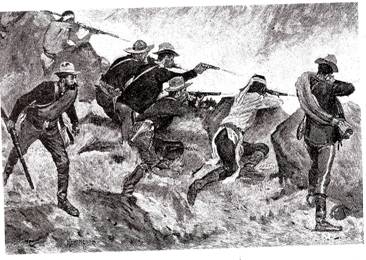

Figure 6 - Soldiers firing down at the cave.

Sketch, "Ross's Attack" by Frederic Remington,

for Century Magazine, March, 1891.

Bourke wrote that the soldiers advanced to find a ghastly scene of slaughter. "There were men and women dead or writhing in the agonies of death and with them several babies, killed by our glancing bullets, or by the storm of rocks and stones that had descended above."

Hoo-moo-thy-ah (Mike Burns) poignantly wrote about the end of the slaughter. "My people thought that they were strongly protected and could not see to shoot the soldiers. But the soldiers were ordered to shoot down volleys of buckets of lead behind those big boulders, so that the walls of the cave would scatter the glancing bullets into the people beneath. The showers of lead simply shattered the people so completely that they could not be recognized as humans. The war songs ceased."

"It happened that only one was left alive. As he had only one shot left, he killed one Pima Indian at noon. He might have killed more, but when he reached out with the barrel of his gun to reach a bag of gunpowder, a bullet or two struck the gun so that it bent nearly double. He was left in a hole helpless. Finally he was shot. He was my brother-in-law. He was never known to have ever missed a shot. He was the last one to be killed, and he was killed like a man."

The Pima and Maricopa scouts rushed into the cave after the last shots were fired and announced all the men were killed, but actually those who were still alive had their heads crushed in with rocks by the Pimas-traditional enemies of the Yavapais. Any surviving women and children were saved by some of the Apache scouts and given to the soldiers. One badly wounded woman, who could not sit on a horse, was left behind and given food and water. But, when the soldiers were out of sight, some Pimas went back and "smashed her head to jelly." Apparently the Pimas and Maricopas wanted to kill the Apaches, too. The Indians stripped the cave and the dead of many weapons, baskets, household goods, anything they could carry away. Any weapons they didn't take were stacked and burned, so they couldn't be reclaimed later by other fighters. The survivors were taken to Fort Grant.

One survivor who later went on to fame as a doctor and leader of the Yavapai people was a small Indian baby who was almost suffocated under the body of his dead mother. He was adopted by a Maricopa woman and later taken in by a wealthy easterner and educated. He is known by his assumed name, Dr. Carlos Montezuma, and was a cousin of Mike Burns.

Then, Brown and his men put away their deadly carbines (Sharp's) and left the dead where they lay. The total battle had lasted about four bloody hours. Three months later the dispirited Yavapai tribe surrended to the U.S. Forces at Camp Verde. The skeletons lay unburied in the cave for almost a half century. Supposedly the name "Skeleton Cave" was given to this cave due to the terrible smell that emanated from the cave for many years and the piles of bones filling the cave. Sixty-one years later a visitor to the cave testified, "the bleached and crumbling bones of the slain still lay in and around the cave."

Even today, accounts differ on the number of Yavapais killed and the number of survivors. On an application form for the National Register of Historic Places (entry that began this article), it states that "the lop-sided casualty ratio justifies the term 'Massacre' in the name of the nomination." Their figures are 54 dead and 20 captured. There were six young girls and an old woman who had left the cave before the attack to examine a great mescal pit down in the canyon and determine whether the food was ready for use, so they survived also. An article in the February 1959 Arizona Highways magazine lists 76 men, women, and children killed outright, another 18 mortally wounded and left to die, while about 35 wounded were taken prisoner. A National Park Service description of the Massacre states there were 75 total killed. An Army report, by Bourke, listed the same numbers as the application form. Another writer said there were 76 dead and 35 survivors. Another author lists 30 survivors. Finally, another historian says there were 66 "Apaches" dead and one warrior who escaped alive was killed soon in another battle at Turret Butte. The application form disputes this, saying, "less probably, a wounded man hid beneath the corpses and later walked to safety." The Yavapai Nation at Fort McDowell, on their web site, states, in one place, that 100 Yavapai men, women and children were killed. But another site claims 75 dead and 25 wounded. "Yavapai consider this the most horrible massacre in their history."The only casualty on the other side was one Pima scout killed and one Pima scout wounded.

Skeletons in the cave

V. AFTERMATH OF THE MASSACRE OF SKELETON CAVE

The Massacre at Skeleton Cave had far-reaching effects on many people - General Crook, the Yavapai and Apache peoples and their chiefs, and later-day visitors to Skeleton Cave.

In Skeleton Cave, the bones lay virtually undisturbed from December 28, 1872 until January 1908. A rancher named Jack Adams led a group of friends to the cave. They found it strewn with the skeletal remains of the fallen Indians. They had a photographer named Lubken with them who took photos of the remains of at least 8 individuals and broken baskets, pottery, metates, hand-stones, fragments of clothing, leather, and blankets within the cave.

A newspaper account of the time has many factual errors, but offers some insight into early reports about Skeleton Cave and the grisly finds in it. A few quotes may be of interest. "Grim and ghostly was the sight that met the eyes of Adams......the whitened skeletons of 200 Indian men, women and children." (Notice exaggerated number of skeletons.) One of Arizona's bloodiest Indian fights is recalled by this important discovery - bloody for the Indians, all of whom were caught like rats in a trap and remorselessly shot to death by Captain John Barnes and his command of soldiers in 1872.....The skeletons found by Adams are lying on the floor of the cave in all sorts of shapes, in heaps and singly. They are male and females from the age of six up.......Jeff Adams (Jack in other accounts) had been a resident of McDowell for twenty-eight years, and since his coming to Arizona had heard of the cave, but never knew its location. He was led to it by first stumbling across the old trail, and by following it. No more terrible massacre of Indians had ever taken place in Arizona.... "

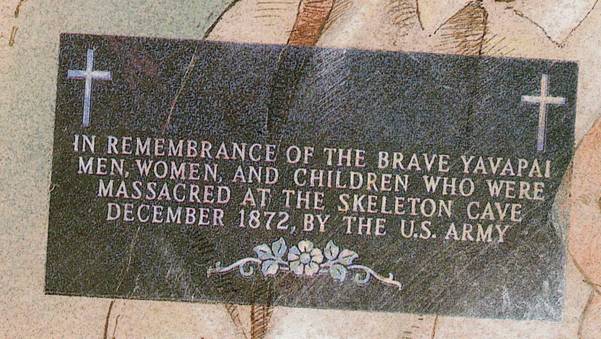

As for the bones, beginning in the 1920s, the bones were removed to the Fort McDowell Cemetery and buried. They were scraped up by Yavapai tribal elders and archeologists, accompanied by a deputy sheriff. Fragments were still being recovered in the 1930s and later. On Memorial Day in 1985, there was a service at the Fort McDowell Presbyterian Church and a tombstone was dedicated over their mass grave. Norman Austin, Fort McDowell tribal president at the time, said the record has never been set straight and that he didn't know what prompted the massacre, but the victims were Yavapais, not Apaches. He laments that "Yavapai youths seem particularly apathetic about inaccuracies in history." He assumed that "their parents didn't tell them about what had taken place some years back.....I was told by my grandfather and grandmother about how the Yavapais came here to Fort McDowell. We're trying to let them know what our people had gone through at that time-how we came about and how many things were sacrificed for we who are living today." .....and later, "There was a lot of punishment and a lot of killing and a lot of massacres. We want to let youths know what our people did for us and have respect for them and respect for ourselves." During the ceremony, John Smith, a tribal elder, chronicled the events that led to the massacre. Smith's parents lived about a mile from the cave at the time of the killings and he witnessed much of the relocation process. The service also included prayers, songs and other tribal ceremonies. The memorial's goal, according to Austin, was "to provide a little back history...about our land. We're all part of it and let's have respect for one another."

Figure 7 - Memorial Plaque at Fort McDowell

Drawing by Luis Tomas in Arizona Highways magazine, May, 1991

General George Crook and his Cavalry were involved in more skirmishes and massacres after Skeleton Cave. One, on March 25, 1873, 3 months after the Skeleton Cave Massacre, was called "Turret Peak" on the Verde River north of Horseshoe Lake. Another battle between the 5th Calvary and the hostile Indians occurred nearby two days later. He instructed his soldiers to stay in the field until they had located and subdued the last Apache." In a macabre effort to capture Delche, whom Crook had erroneously believed to be hiding in Skeleton Cave, he offered rewards for heads of important hostile chiefs. Delche had an especially high price on his head. A famous drawing by Frederic Remington, entitled "The Head Delivered", shows a head being brought by Indians to Crook's camp. He paid the reward three times - a different head each time! None of the heads belonged to Delche.

Finally, a Peace Treaty was signed with the Apaches at Camp Verde, Arizona. The Treaty gained Crook the rank of Brigadier General. The warfare was too much even for the Apaches. They concluded that peace on the Reservation was better. On April 27, 1873, the last of the Apaches surrendered at Camp Verde. An Apache-Mohave chief named Chalipun approached the General and explained, supposedly, "You see, we are nearly dead from want of food and exposure - the copper cartridge has done the business for us. I am glad of the opportunity to surrender, but I do it not because I love you, but because I am afraid of the General."

Crook's old enemy, Delche, surrendered also. His 125 warriors had been reduced to 20 after six months of warfare. He complained, "There was a time when we could escape the white soldiers. But now the very rocks have become soft. We cannot put our feet anywhere. We cannot sleep, for if a coyote or fox barks, or a stone moves we are up - the soldiers have come."

As the soldiers took their captives back to Camp Verde, accounts say "an unprecedented thing began to happen. Each procession was joined by hundreds of 'wild' Apaches. In twos and threes they quietly slipped among the marchers, uttering only the word 'Siquian - my brother' to the scouts who had hunted them. When Crook counted all the hostiles who had come in, he found that he had 2,300 captives."

Crook, according to Bourke, then told the leaders in "his firm paternal way" that "if they would live at peace on the Reservation, he promised he would be the best friend they ever had. " Most of the bands agreed to move onto a reservation at Fort Verde.

Following his great success, Crook was transferred out of Arizona in 1874 as Commander of the Department of the Platte from 1875 to 1882, with headquarters at Fort Omaha, Nebraska. He began to speak out on behalf of Native American rights.

Crook returned to Arizona in 1882. The last Apache battle was fought in Arizona at Big Dry Wash, a few miles north of General Springs on the Mogollon Rim. This battle, on July 17, 1882, marked a major Apache uprising. That September, Crook was recalled to Arizona to bring in Geronimo. In March,1886 there was an incident where Geronimo met with Crook and agreed to surrender at Canon de los Embudos. But, convinced Crook would kill him, Geronimo gathered a few warriors and slipped away. When the General of the Army, Phil Sheridan (Crook's friend from West Point), questioned Crook for placing too much trust in Geronimo, Crook resigned. He was replaced by another seasoned Indian fighter named General Nelson Miles, apparently an egotistical and politically ambitious soldier, who took false credit for the eventual capture of Geronimo and used it to advance his career. Politics had ended Crook's career in Arizona.

Also, as an aftermath of the Skeleton Cave Massacre, according to Charles Lummis, an early reporter for the Los Angeles Times who covered the final days of the Apache War, Crook was "reviled by many Arizonans at the time. Though earlier in his career, he had developed a reputation as a ruthless Indian fighter, in the waning days of the Indian wars he had grown increasingly sympathetic toward his erstwhile enemies."...."And once a group of renegades was cornered, Crook or his officers would approach unarmed, and after convincing them to turn themselves in, he would let them keep their weapons." The Tombstone Epitaph , in particular, "hated him for his 'soft' approach, and even national papers grew critical as months passed and Geronimo remained on the loose." Crook's "suspicious affinity" for his Apache charges, and his "curious refusal to go for the kill when his troops seemed to have the renegades boxed in" suggested to the paper that the "veteran Indian fighter had fallen dangerously under the sway of 'hypocritical kid-gloved philosophers ' of the East. New England humanitarians believe-or profess to believe-that the whites are the aggressor. When the Indians kill whites, they intimate in as many words, that it serves us right for maltreating their pets. If it were only possible for Geronimo to go on one of his murderous raids in the eastern states, the Indian problem would soon be solved."

Finally, near the end of Crook's career, the San Francisco Chronicle was less hysterical but no less critical, reflecting a growing consensus about Crook's performance in 1886, 14 years after the Skeleton Cave Massacre: "His mismanagement of the Apache campaign has cost him not only advancement in rank but a large share of his reputation as an Indian fighter."

VI CONCLUSIONS; HISTORIANS DO NOT AGREE

This article has presented emotional accounts by one survivor, Hoo-moo-thy-ah (Mike Burns), the boy who led soldiers to Skeleton Cave and witnessed the massacre of his people; writings by Captain John G. Bourke, an aide de camp glorifying his General; excerpts from a graduate thesis for the U.S.Army Command and General Staff College in 1978 about General Crook and his strategies in warfare; writers Daniel Joseph Bangs and Donald Bangs, for Arizona Highways magazine of February 1959, and a subsequent briefer article in Arizona Highways magazine in May 1991 by Jim Schreier, newspaper accounts of the Apache warfare of the times, and several historians writing in books and in articles on the Internet. Who has all the facts? Who is truly telling the story of the Skeleton Cave Massacre impartially? Writers about the event, as noted, disagree on many "facts", even the number of victims.

In my opinion, based on much research, the Arizona Highways article of 1959, written before all the known "facts" emerged through the mists of time, has the most errors. For example, the Yavapai are consistently referred to as Apaches. Details about the actions of the scouts, who were Pima and Apache, and their murders of some of the survivors are omitted.

The account by Mike Burns in his autobiography, published in 2002 long after his death in 1934, was apparently written in hard-to-read English and was read only by a few historians. His intense emotion at seeing his family murdered understandably colors his account. Yet, it would be valuable as a first-person witness to events.

General Crook's aide, Bourke, by all accounts was very devoted to his General, and wished to present events in a light most favorable to him. And a much, much later account of successful use of tactics written for the graduate thesis at a military college, obviously glorifies the Cavalry's success. So does an internet account on use of the Sharp's rifle in the battle.

Most of the other historical accounts available in history books, i.e. Marshall Trimble's Arizona: A Cavalcade of History (1989) and on the Internet, tend to build on each other to form a fairly similar story of the Skeleton Cave Massacre.

Still, who can really know all the events and motivations of the tragic Skeleton Cave Massacre so long ago on Christmas Day, December 28, 1872? They followed a general pattern of battles between military and civilians and Native Americans of the late 1800's. As Arizona developed into a state, the Skeleton Cave Massacre that turned a shelter cave into a graveyard should not be forgotten.

VII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This author, Kathy Block, wishes to credit the thought-provoking article by George A. Brunson, "Some Thoughts About History" on Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project (APCRP) web pages for inspiring this attempt to tell the tragic story of the Skeleton Cave Massacre. Also, a big "thank you" to Mr. Tom Guilleland of Tucson, Arizona for supplying Xeroxes of important source materials and reviewing this article, and also to Allan Hall and Bonnie Helten of APCRP for their thoughtful suggestions. Finally, my appreciation to my husband, Ed Block, for his proofreading and patience while I worked many hours researching and writing. Any errors in interpreting materials are my own.

VIII BIBLIOGRAPHY

Because this was not a formal research paper for publication in commercial media form, I did not use annotated footnotes and references to some materials quoted or paraphrased in this article. Occasionally I indicated direct sources, such as Bourke. Sometimes Internet articles had no author.

I often combined materials from many sources in one paragraph or even sentence.

Main Books Used for Information:

Martin F. Schmitt and Dee Brown. Fighting Indians of the West. Bonanza Book, New York, 1968. Chapter "The Conquest of Cochise", pp.91-94. The detailed, vivid account consistently referred to the Yavapai as Apaches.

Marshall Trimble. Arizona: A Cavalcade of History. Treasure Chest Publications, Tucson, Arizona, 1989. "Chapter 8: Turbulent Times," pp.116-118. General, but sparse, outline of events.

Smithsonian Institute. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 30. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Ed. Frederick Webb Hodge. Part I, 1907, pp.63-68; Part 2, 1910, p.994. Useful for insight into ethnological viewpoints of the time.

Other Sources of Information:

Daniel Joseph Bangs and Donald Bangs, "A Trip to Skeleton Cave," Arizona Highways magazine, February, 1959. Detailed information on the physical location of the cave, interesting historical photos, but some inaccuracies, also. Called the victims "Apaches".

Jim Schreier, "The Skeleton Cave Incident", Arizona Highways magazine, May 1991. Focuses on Hoo-Mo-thya (Mike Burns) and his life and thoughts from his autobiography, which had not been published from his manuscript at this time.

Mike Burns. The Journey of a Yavapai Indian: A 19th Century Odysey. Random House, 2002. I did not quote directly from this book, but rather from long excerpts from it on the Internet.

"The U.S. Cavalry Versus the Indians, 1832 through 1898," Seniram Publishing, Inc. Glenside, PA. 1989. From excerpts printed on the Internet from "A Portrait of Stars and Stripes" which may be used and reprinted by students and for non-commercial use by the individual. Very useful as a guideline to battles and events involving General Crook and the 5th Cavalry.

Application for National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service, 1990, Prepared by Norm Tessman and Alan Ferg of the Arizona State Historic Preservation Office. Generously supplied by Tom Gilleland of Tucson, Arizona. Offered much basic information about the cave and the Massacre.

Wikepedia web sites for biographies of General George Crook and Captain John Bourke, information on the Yavapai people, Fort McDowell, and the Skeleton Cave Massacre in general. These were supplemented from other Internet materials.

Stan Brown, "Back when the Yavapai Indian Reservation was Established," Payson Roundup, Oct.21, 2003, Internet Article.

Mark Thompson, "Lummis and the Apache War," 2001. Article from the Internet.

Bill Heidner, "Apache Scouts Lead Army to Success in Arizona." 2005. Article from the Internet.

William Gruaberg, "General Crook and Counter-Insurgency Warfare," Master's Thesis, U.S.Army Command and Staff College, 1978, pages 5-6 and 46-47, Article from the Internet. A good view of military strategy from a military viewpoint.

"The Skeleton Cave Massacre," Desert USA, 2006. Focuses on use of Sharp's carbines in the Skeleton Cave Massacre and other battles, from viewpoint of their effectiveness and technological advantages.

"The Only Good Indian is a Dead Indian," from Answers.com. on the Internet.

Wiccan site, "The Arizona Ghost Searchers," article on Camp Grant. Internet Article.

Legends of America web site: "Fort McDowell-in the Midst of the Apache Wars." by Kathy Weiser, Jan. 2009.

Peter Aleshire, "Scenic Wonders, tragic history," Payson Roundup, Oct.22, 2008. Internet Article.

Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, "Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation," Internet Article.

National Archives Learning Curve web site, "George Crook." Internet Article. Details about General Crook's life, with comments from various individuals he encountered in his lifetime.

National Park Service web site, "Soldier and Brave: Survey of Historical Sites and Buildings." "Salt River Canyon (Skeleton Cave) Battlefield, Arizona." Internet Article. also, from same site, "Camp Verde, Arizona."

Bill Heidner, "Apache Scouts Lead Army to Success in Arizona," Yuma Proving Ground web site, Dec.7, 2005. Internet Article.

David Roberts, Once They Moved Like the Wind: Cochise, Geronimo and the Apache Wars. Barnes and Noble, 1994. From excerpts published on the Internet.

American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project

Internet Presentation

Version 061309

Revised 040312

WebMaster: Neal Du Shane

Copyright

©2003-2012 Neal Du Shane

All rights reserved. Information contained within this website may be used

for personal family history purposes, but not for financial profit of any kind.

All contents of this website are willed to the American Pioneer & Cemetery

Research Project (APCRP).

HOME | BOOSTER | CEMETERIES | EDUCATION | GHOST TOWNS | HEADSTONE

MINOTTO | PICTURES | ROADS | JACK SWILLING | TEN DAY TRAMPS

.